My mother almost died from an abortion.

There were already six children in our little 830 square foot house, and a seventh one was not acceptable to my father. Joyce, who I called Ma for all her days, had earlier decided to take control of her life away from, James, my violent and abusive father. After five kids, Ma underwent a tubal ligation to prevent another pregnancy but the surgery failed and my youngest sister was born. The problem might have never materialized had Daddy been willing to use birth control but his refusal led to a seventh pregnancy. Ma was fearful of what his reaction would be to the news, and her emotions were justified.

“We ain’t havin’ no more damned kids,” he said. “I can’t afford ‘em, and I don’t want ‘em.”

“Well, what do you suggest I do?” Ma asked. “I didn’t do this by myself.”

“You get rid of it, that’s what you do!”

He did not immediately have an answer for how she might accomplish that, but Daddy got a payday loan for $100 and came home from work and gave it to Ma with strict orders how to use it.

“Take this and find one a them doctors or whatever they are that get rid of babies before they are born,” he said. “I’m going down to Mississippi to see momma and when I get back, I want that baby gone.”

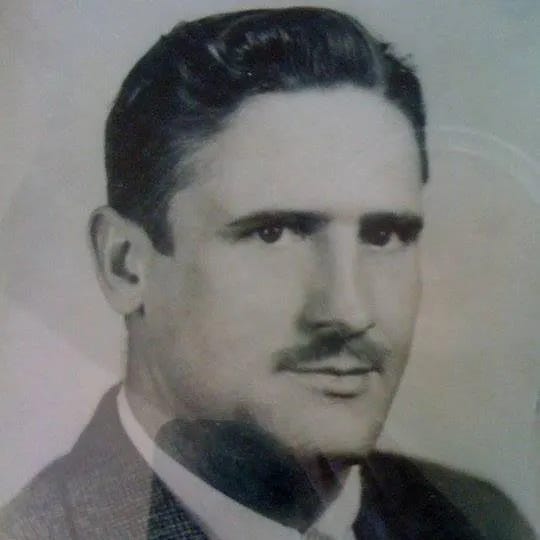

My father was not an irresponsible man. He worked hard every day of his life and did what he could for his family without an education or privilege. He was, however, mentally unstable, and had harmed his wife, and, sometimes, his children, with outbursts of anger. His lack of concern for his wife’s safety in a cultural era where abortion was illegal and practiced in backrooms and alleyways still disturbs me after more than a half century.

Ma did not want another child, either. She wanted a divorce but was afraid her husband would beat her again if she suggested the idea. We do not know how she found an abortionist, but she left on a Friday evening and told only her second oldest child, Beverly. Through contacts at the restaurant where she was a waitress, Ma was connected to an abortionist up in Saginaw. I always assumed one of the truck drivers who stopped in where she worked gave her a name, but I only got pieces of this story much later in life. Ma did not ever speak about it directly with me; my sisters did.

“She was gone Friday and Saturday nights,” Bev told me. “And I had no idea where she was, only what she went to get done. But when she didn’t come home Sunday, I started thinking about calling the police. But what would I tell them?”

I have never been able to comprehend what my mother must have felt, arriving alone at a motel in a factory town, meeting a stranger who was about to perform the most intimate and personal procedure imaginable. I doubt she knew or considered the danger but I am certain she was fearful. I know my mother would have grieved the unborn child, but she would have been equally frightened about adding to her family with a man she no longer loved, and who was prone to fits of rage. She had been forced into a frightening, and even life-threatening position by men who had enacted laws that made no sense, and by the man who had impregnated her by his refusal to use contraception in his marriage.

Ma nearly bled to death in a rundown motel room. I was told she was barely conscious when she was discovered by a housekeeper. We did not hear details of what medical care she received but Bev said she was pallid and fragile looking when she had returned. The fear of Daddy’s temper and any threat of violence she might have faced for having another child had been exorcised.

A few weeks after Ma had the procedure, whatever it might have been, the local newspaper ran a story about an abortion doctor in Saginaw who had been arrested for running a clinic out of a motel. Pictures were of dark filthy rooms with trash and rumpled blankets and tossed bloody towels. I do not know if my mother ever saw the story in the paper because she had gone back to work right after returning home. She had no choice. Perhaps, it was a different abortionist who had been arrested. Those people moved constantly and were proliferating across the landscape, making money and killing women, in a time when the law was unbearably absurd.

My parents had been caught up in the optimism of that age, though. Using his VA benefits, they got a mortgage to buy our little house, which had been set in a former bean field with a few hundred others of similar design and construction. The white Dixie diaspora filled up the neighborhood where every home had a cedar sapling in the front yard and a flowerpot below the large picture window. They were opaque coverings, though, for the psychological and physical hardship of making it in America during that era.

I think my father had been broken before reaching manhood. One morning while chopping cotton at age sixteen, he had a nervous breakdown and was driven to Memphis by his parents, put into an asylum for six months, and ignored. Leaving for the European Theater of World War II must have felt like liberation but walking across France and killing other young men certainly did not improve his mental stability. He brought my mother home to the South with him from Newfoundland and they spent four years as cotton sharecroppers before surrendering to economic realities and going north to look for work in the factories as part of the Great Migration.

“No running water or electricity in that shack in the cotton fields,” Ma told me. “I had never even seen an outhouse before, son. We could see the stars at night between the slats in the roof and we tacked newspapers over the spaces between the wall boards when it got cold in the winter. You know I thought I was going to a big house with white columns and a balcony, and I figured your dad managed a giant farm or plantation or whatever. I was glad to leave.”

I do not know where my father’s violence originated but suspect it was an anger at the difficulties he constantly confronted. When we were just kids, he was institutionalized three times and endured 24 electroshock treatments and was once taken out of the house in a straight jacket after he had thrown the kitchen drawers through the living room windows. I remember my little brother kneeling in the broken glass, picking up forks and knives and spoons and trying to place them back in their proper trays as if he had the ability to return some order to our lives. That was the incident that brought their troubled 21 year marriage to an end.

My sense has always been that I repressed the details of this fight in my memory, but I began to recover images and language when I spoke about it with my sister Beverly, who was at college when this happened.

“….ain’t gonna put up with your goddamned lyin’ about it no more….”

Daddy had on his fresh work clothes and looked like he was ready to leave but had decided to stop and attack his wife before he punched in on the time clock at the factory.

“I didn’t do anything, Jimmy,” Ma held her hands up to protect her face against her husband’s slapping and punching.

“Stop it, damnit. Please. You’re hurting me.”

My little sisters and brother were screaming and crying behind me, “Daddy, stop. Don’t hurt, Mama.”

I was between them by the stove, scared and stunned by my father’s great animosity. He grabbed Ma by the shoulders and slammed her back against the wall. Her head hit with enough force that it could have dented the sheetrock. I ran to Daddy and pressed against his waist and started swinging my arms and fists against him.

“Don’t hit my Ma, Daddy! Stop it. Please stop it.”

He pushed me away, backed off from Ma, and grabbed the broom from next to the back door.

“I don’t gotta put up with your cheatin’ and lyin’ no more,” he said.

Daddy held the broom handle at both ends, lifted his knee, and cracked it in two with a loud snap. The pieces had sharp, pointed edges to the wood, and he took the one without the brush on it and moved slowly toward my mother, raising it up in a threatening manner.

“Jimmy, Jimmy, my god, what are you doing?”

She had barely recovered her senses from being slammed against the wall when she saw him coming at her with the pointed broom handle and wielding it like a knife.

“You ain’t lyin to me no damned more.”

My father was almost growling. Ma moved to get away and he caught her with one of his big arms. I could not stand the sound of her fear and jumped up again at my father, hitting him in the stomach with my small ten-year-old fists. He ignored me, and when I looked up at him with my pleading face, I saw him bring down the wooden broomstick like a knife just as Mom raised her arms to protect her face.

This stabbing action plunged the wooden shiv several inches deep into the soft flesh of her forearm, and a gusher of blood rushed out and down to her elbow and the floor. I remember her scream as a howl and Daddy pulled the broomstick free from her arm and stepped backwards with me still clinging to his belt. He hit me with his open hand and knocked me to the floor and slammed my head against the stove, which put me in and out of consciousness. I heard Ma and the girls crying and saw Daddy’s feet as he left the room.

“I thought your dad was going to kill me that day,” Ma told me when we finally talked about the incident. “I don’t know what made him stop. Maybe it was just the blood. I don’t even know what started it all. I think he was accusing me of being with one of the customers at the restaurant or something. I was scared of what was going to happen next because I always let him back into the house after we fought, even when the police came.”

She had regained enough composure to call the police and tell them she needed an ambulance, and she used a wet washcloth to hold over the flap of loose and bleeding flesh that Daddy had dug out from the bone in his anger. I rode with Ma to the emergency room and while her arm was stitched back together, I was checked for a concussion. The police also asked Mom if she were ready to file charges this time against Daddy; especially since his offense was so horrid, and to let him get away with such behavior might be putting her life and the lives of her children at risk.

Mom remained hesitant. She had come of age as a child raising children and had no guidance from anyone other than the husband who had hit her. I do not think she knew what her best choices were. Like many abused women, she probably kept hoping my father would change and she would never again be hit, and they could begin to build their happily ever after. More than fifteen police calls to the house did not seem to cause her to waver, until Beverly convinced her there was no hope for her marriage.

My mother found the courage to file for divorce after Daddy was arrested and sent back to the state hospital for more treatment. She did not falter, though, as a parent raising her six children. Mom got a loan to buy a small coffee shop and became a businesswoman in the early sixties, a relatively uncommon experience for the time. The restaurant required 14–16-hour days, though, and the factory workers who stopped by daily introduced her to Benzedrine to stay awake and work. An eventual addiction led to her collapse, and she was later diagnosed with a debilitating form of cancer, and she lost her restaurant. I came to feel as though every dream she ever had fell away from her, except for her children.

In a grotesque fashion, the national politics of this part of my life have set me to thinking much about my mother in recent days, and of the other women who, even today, are enduring such dangers. Trump, and the radical conservatives who kick their jack boots to salute his political whims, are the type of people, generally white males, who nearly killed my mother with absurd laws robbing her and all American women of their rights. Women confronting problem pregnancies do not need to be driven to unlicensed butchers and dead-end shamans because of the religious beliefs of a minority. I might have lost her. My brother and sisters might have lost her, and all because one man thought he controlled her body and other men made laws that exercised that control. My mother’s problems were horrendous and beyond my understanding, but probably not that uncommon. Families are often a mess, marriages frequently imbalanced. Countless times, they become traps.

My father seemed to slowly achieve a kind of grace with his electroshock and the shame of his own behavior disappeared from his memory. He went home to Mississippi to listen to the woods and grow tomatoes and corn, but he bought two burial plots up in Michigan. Behind his uncontrollable rage, there lay the interminable connection to the only woman who had ever shown him love, and, in the end, he wanted her beside him, eternally.

Mom refused his offer into her early eighties, but as the lights of the world dimmed for her, she began to think differently, and let it be known she wanted to be next to the handsome soldier who had come into her house out of the cold in Newfoundland. She was put to rest beside him, and just walking distance from the little house where they started out dreaming.

I wish they had another chance.

Jim Bob, your essay is the most powerful argument for “Kamala” and against “Trump” without focusing on them as individuals that I have read. Thank you. Dave

Blessings, Jim Bob. Your raw story brought tears. It's a story that far too many women know all too well. You have done a favor for your mother and all the other women who have suffered through the hellish days, nights and years brought on by men who learned from the patriarchy that women are less than and only here on earth to satisfy the predatory nature of males. I am grateful that men like you who lived and witnessed the constant degredation of women in your family chose instead to throw off those shackels and indulge in love, kindness and respect as ways to treat the women in their lives.