(I’m going to try to offer up material midweek. I am as weary of our politics as anyone but also feel an obligation to offer up perspective. My interest, though, primarily, is to write stories that appeal across a broad spectrum of readers, not just politicos. This week I am dispatching a piece from last summer about my time West of the Divide and an adventurous attempt to go drinking with Doc Holliday. I thought this would appeal to some of the new subscribers who almost certainly have not seen any of my non-political writings. - JM)

We were up above the Great Divide and flying west to where the clouds were parting after a rain shower. I noticed the pilot pull pitch slightly on his collective and the nose of the Bell Jet Ranger helicopter rose a few degrees into a gentle climb.

“Let’s go there,” he said into our headsets, and he pointed northwestward. “There’s a rainbow over there.”

“I don’t see it,” I said.

“Look again, then. It’s about fifteen degrees to your right.”

By the time the light prism made by the humid summer air and the clouds had tossed the colors across our front, we were almost to our destination, but there was another distraction. A large herd of elk were running along a creek filled with late spring snow melt and we came around enough to take in the view without frightening the animals.

“If this is a sales job,” I said. “I think you can move to close now.”

“Nah, it’s just Colorado. Sells itself, eh?”

I was moving to the mountains to make a home. A job offer was about to be put in front of me after I had gotten attention by winning a prestigious journalism award from an Ivy League university. When my plane had landed in Denver, I was shuttled over to the waiting helicopter where the TV news executive and the pilot were discussing what restaurant they might choose for our dining that evening.

As overwhelmed as I was with the corporate seduction, I thought about my young bride waiting on news of our future. When we had begun dating at the university up in Michigan, I talked often about my love of the mountains that I had seen while hitchhiking across America and my dreams of continuous motorcycle adventures down narrow two-lanes toward new horizons. A farm girl from a small community with a grain elevator, a school, and grocery store, she was intrigued, and created a triad of the letter “M” in my dreams.

“Mountains, motorcycles, and Mary Lou,” my friends pointed out.

“And in that order,” she often added.

The television station gave me an office in a corner room on the ground floor of the Hotel Colorado in Glenwood Springs. The news executives wanted to be the first Denver station to broadcast live from the Western Slope, which meant I would frequently be making the 90-mile run down Interstate 70 to Grand Junction where the only microwave video link had been established. I did not take an accurate reading of the situation and its potential challenges, but it did not matter since I had found myself in the mountains with an ascendent career in TV journalism. I was joyful about an opportunity to explore the West because every square mile of territory on our side of the Continental Divide was included in my assignment. There had to be great untold stories to share, history to relate, and issues to confront. I was not quite thirty years old and felt well pleased with my fortunes.

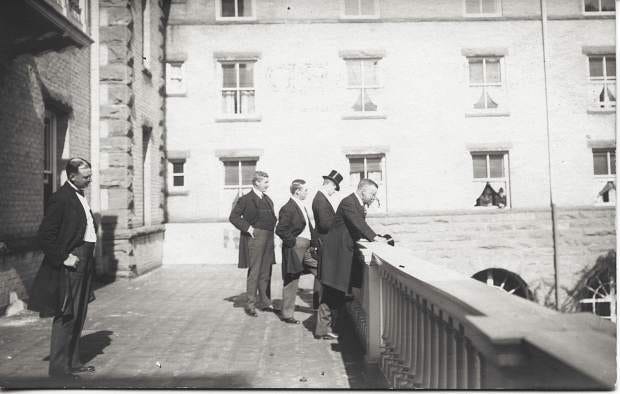

The hotel was a favorite of President Theodore Roosevelt, who stayed there during his many elk, bear, and mountain lion hunting trips to Western Colorado. In 1905, he decamped Washington for three weeks and was absent so long that the hotel, referred to locally as “The Grande Dame,” was suddenly called the Western White House. The structure was built hard by the geothermal hot springs adjacent to the Colorado River, which comes down through Glenwood Canyon, and was an attraction for the thousands of adventurers who had crossed the Rockies in a gold and silver mining stampede. The sulphureous water was said to give off curative vapors.

Roosevelt on the Courtyard Balcony of the Hotel Colorado

I was drawn to the history, of course, and still am, but TR was always a troubling contradiction for me. While he created the National Park System, he was an adventurous war monger. His capriciousness in Cuba had no real purpose but he always felt that war was defining for a man, and peace was of no great value when it came to the development of character. Roosevelt was so enamored of war that he encouraged his sons to enlist for World War I, a choice that was to bring him much grief. Quentin, the youngest Roosevelt child, became a pursuit pilot and was shot down and killed during aerial combat over France. The loss also probably cost the president his life. TR’s robust health failed him in his sadness, and he was dead in about a year.

“Cool pics, huh?” I was standing on the edge of the hotel’s lobby admiring the black and white framed shots of Roosevelt from his 1905 expedition.

“Yeah, pretty great.” I smiled and turned back to the photos.

“Name’s Kevin,” he said, and stuck out his hand before I had turned in his direction.

“Oh, hey, nice to meet you.”

“You staying here on a visit?”

“More than that, actually. I’m living and working out of the same office down the hall.”

“Well, that’s kind of weird. I live here, too. Second floor. But I work outside the building in construction sales.”

“I guess we’ll see each other around.”

“You know about the Doc Holliday stuff?” The question seemed abrupt.

“A little. But I intend to learn a lot more. Gonna be living here, and I was always interested in his story.”

“Hey, cool. You have any interest in walking across the bridge into town for a burger and a beer? I’m kinda tired of eating the hotel food here.”

Kevin was energetic and slender with thin blonde hair already receding across the front of his forehead. I thought he was fit, and he talked fast without asking questions seeming almost in a hurry to get to the beer joint while I took my time crossing over the Colorado and listening to its gentle roar beneath the foot bridge gratings. Kevin turned around and waved me forward, impatient with my saunter.

“Yeah, so Doc Holliday is buried here in Glenwood.” Kevin had knocked back half his beer before I had taken a sip. “He’s on a hill just off the road a bit.”

“I knew he had died here, but I didn’t think they’d verified he was buried in Glenwood.”

“You don’t think the city would let him go, do you? They are turning the old drunken, gunslingin’, card playin’ dentist and TB patient into a tourist attraction.”

“I am pretty sure I read a magazine piece that said his hometown over in Georgia is disputing all that. They said there’s evidence Doc’s father came out here to recover his body and bring him home to the family cemetery.”

“Yeah, can’t blame them, either” Kevin said. “I imagine Southern Georgia needs a few tourist attractions.”

Kevin was four large beers into the evening before I’d finished my first and his energy level had not abated. While I nibbled on fries, he ordered a scotch and put aside beer for the evening. Within thirty minutes, three more scotches had run down his gullet and Kevin was asking for our bill and telling me he had something he needed to take care of. I watched him walk out the door into the western gloaming and wondered if I had made a friend or encountered a mystery.

There was nothing surprising to me, though, that I had found myself at the end of Doc Holliday’s trail. I had been obsessed with the American West and its stories since I was tall enough to reach the channel dial on the TV up in Michigan. My father loved to watch westerns on our boxy, used Zenith TV, and spent long hours on a vinyl sofa staring at Randolph Scott riding the range alone. He was never happy when I expressed my sympathy for the Indians.

These movies were the only time in which I thought I knew Daddy and that he might have an interest in his eldest son. He talked about the horses and the guns and the landscape as though he had ridden the same trails and I asked him questions about the broken country and how to shoot. In my adulthood I was saddened my father had not been born a century earlier because he cared only about an open sky and freedom from the things that destroy a man’s dreams. I thought the West might give me a closeness to him, but I became a son not worthy enough to distract him from black and white stories where rifles and cowboy hats rewrote history, or maybe that was the only escape he had from the factory, and he did not want to avert his eyes to one of his six children.

I got too busy to pursue Doc’s myth. My photographer, Tommy, and I spent our hours driving the winding mountain roads or jumping into a single engine Cessna, bouncing around in unstable mountain air, chasing stories and hurrying down to the microwave link. I thought about Kevin’s mention of Doc’s death and discovered that he had passed at the old Hotel Glenwood, which was not the building housing my office. Holliday’s journey as a dentist trained in Philadelphia, who contracted tuberculosis while he cared for his dying mother suffering from the same affliction, had always fascinated me.

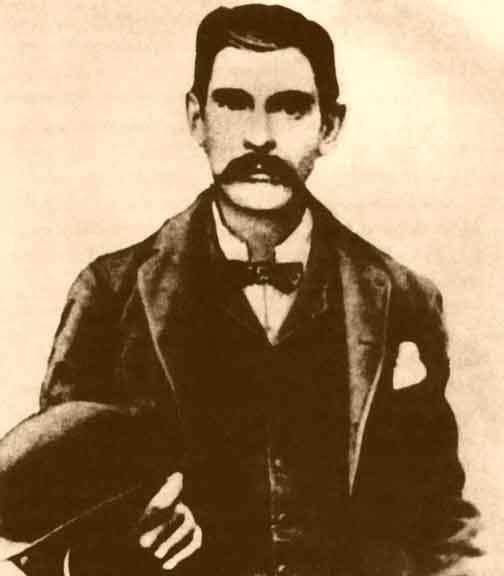

Doc was a man who did not need a myth. His life was equal to the epic expansion of the West and the rule of the gun when law was unavailable. He did, of course, stand into the haze of bullets at the OK Corral with his friends the Earp brothers, but he did not kill a dozen men during his short life, as the legend wants us to believe; only three have been verified. A warrant was issued claiming he had slain one of the “cowboys” from Tombstone, but Doc had left Arizona for Colorado and Wyatt Earp’s old friend Bat Masterson managed to convince authorities there was not enough reliable evidence to extradite Holliday for prosecution.

John Henry “Doc” Holliday

Doc wandered across the face of the West, playing faro at card tables, drinking, and taking laudanum to ease the pain of his constant coughing up of blood. The time he spent in Texas, trying to practice dentistry in Dallas and a few other frontier towns, had not unfolded as he had hoped, and he kept drifting, slinging cards, drawing his gun just as quickly, and doing his best to resist the destiny he faced as a victim of TB before there was any reliable treatment. Nothing ever worked for Holliday as well as drinking, gambling, and pistols and when he settled toward his natural inclinations, trouble ensued.

“Hey, where have you been?” I had spotted Kevin after a few weeks of his absence, standing at the coffee service in the hotel lobby.

“Eh, just running around doing sales. Wears me out.”

“I wondered. Haven’t seen you around the hotel. Stopped by your room and knocked on the door thinking you might want to grab dinner. Not really meeting many people out here.”

“Yeah, it’s tough. I get it. You wanna grab a bite after work today?”

“Sure. I don’t have to go to Junction this evening since I filed a taped report. So, yeah, lemme know.”

I suppose I knew less about Kevin than I did Doc. We had only hung out two other times at different beer joints and when I asked questions about his background, I was never certain of the answers. Friendships built on vagaries did not work for me. Each time I had spent socializing with Kevin had involved alcohol and at a certain point he had told me of his urgent need to leave and deal with a nefarious matter he chose not to explain. I was not much of a drinker and thought maybe he did not find me a suitable consort. How was I supposed to know him? His presence seemed more about entertainment than any kind of meaningful relationship.

Doc, I was beginning to know, if not understand. Had he not contracted TB, Holliday might have become a genteel dentist in Griffin, Georgia, unknown to history. Instead, he kept running west, as if there were a strategy to stay ahead of his destiny as a “lunger.” Because no physician knew precisely how to treat TB, they recommended drier air with low humidity as a palliative. Doc didn’t want to die, though. He rode up into the mountains of Northern New Mexico and found the hot springs outside of Las Vegas, hoping the theoretical nonsense of medicine in his era might be right that the steam and vapors of Sulphur could change the course of his life. No such thing worked, though, so he played the tables, gambled, argued, and ran from responsibility, undoubtedly angry that he was being robbed in a manner more despicable than any ambush by a highwayman.

Even as he staggered across the West from low oxygen in his blood, Holliday continued to drink and smoke and gamble, determined to take what he considered enjoyment while it was still available to his faltering mind and body. There is little doubt that he was angry over the cards he had been dealt by fate and maybe every hand of faro was his attempt to beat the odds that indicated he was doomed.

At a time when Doc said he was 550 miles distant, the body of outlaw and gunfighter Johnny Ringo was found in the low crook of a tree with a bullet in his temple and a six-gun dangling from a finger. A coroner ruled the death a suicide but there were several people who insisted Doc and Wyatt were back together and had ridden Ringo to the ground near Chiricahua Peak in the Arizona Territory. The story doesn’t hold up well to scrutiny since there was still a murder warrant out for Doc, and he likely would not have risked entering Arizona. He had been accused of killing one of the Cowboys from the OK Corral shootout. Holliday had joined the Earps on a vendetta ride to eliminate their aggressors from Tombstone and came upon one hiding near a train platform in Tucson, waiting to kill Virgil Earp before he boarded for California. Instead, Doc was said to have shot dead Frank Stillwell, the potential assassin.

The Movie “Tombstone’s” Version of Doc and Johnny Ringo’s Meeting

After playing the tables in Denver, Doc drifted up to Leadville, an attempt to take advantage of the prospectors who had moved into the mountains trying to create another California Gold Rush. Described as “skeletal” by witnesses, Holliday got into a confrontation with a barkeeper over a five-dollar loan Doc had been unable to repay. The man, Billy Allen, was authorized to make arrests at his Monarch Saloon, but Doc had failed to show, and Allen had decided he was going to find the gambler and get his money. He could not, however, carry a gun outside of his establishment.

Doc was waiting on Allen at Hyman’s Saloon, just down the street, after telling the Leadville Marshall Henry Faucett about his plans for Allen, who outweighed the ectomorphic Holliday by fifty pounds. “I’ll just get a shotgun and shoot him on sight.” Instead, he used a pistol when Allen, a former police officer, entered the door. Holliday’s second shot hit the unarmed Allen and severed an artery in his arm, which began profuse bleeding. The injured man survived when his artery was sewn back together, and Doc was later acquitted of wrongdoing in a trial. His defense was based a Western credo called, “No Duty to Retreat,” which was a law enacted by states that when a man was without blame for provoking a confrontation that he had no obligation to flee from his assailant and was not held responsible for consequences. The measure is the historical pre-cursor of the “Stand Your Ground” laws adopted in this century.

“Hey, I’ve got an idea.”

Kevin was sitting across from me in a rumpled white shirt, looking just a bit bleary. The bar had a broad window, and the early autumn sky in late afternoon was pristine and sharply blue in the lowering sun. I could see Aspens on the banks of the Colorado that had already gone yellow.

“What is it?” I asked.

After our late Saturday lunch, we had lingered over beers, but Kevin had already put away multiple scotches. I still did not know much about him other than his employer and hometown and had given up pressing him for information, which seemed to make him uncomfortable. My sense was that whatever his idea might be that I would be disinclined to partake.

“I’ve got a good bottle of scotch out in my truck,” Kevin said. “And some paper cups. Let’s walk up to Doc Holliday’s grave and give him a toast.”

“Now that’s a great idea,” I said. “Is it a long hike? You are a bit drunk, pal.”

“I know, but I can make it. Let’s go.”

My friend swayed along the sidewalk and stopped to steady himself at the trailhead, which climbed several hundred feet above Glenwood Springs proper. The distance was only about a third of a mile, but Kevin had to catch his breath and lean against trees a few times during our ascent. I carried the bottle and cups, and stayed close in case he started to fall, which was becoming increasingly probable.

Just as I thought he was about to quit, we came upon the graveyard. A wrought iron fence enclosed a small number of tombstones. Doc’s stood out, an obelisk that rose above the other nearby mortals, bearing nothing more than his dates of birth and death and his full name, John Henry Holliday. There is no certainty on the exact location of his grave, even if his remains are on the Glenwood hill, though most historians insist he is somewhere at least near his memorial stone.

“Doc damn Holliday,” Kevin said, recovering his breath from the climb. “I guess you are supposed to be quiet and reverent at a graveyard, but I don’t think Doc would give a shit.”

“I’ll open the bottle and let’s toast his legend, instead of his truth, whatever that might be.”

I poured the scotch into Kevin’s unsteady cup and then mine and we raised them in Doc’s direction. He looked at me, blankly, as if expecting me to make the toast but I waited briefly for him to speak, and I did not have much to say.

“Well, here’s to you, Doc,” I said. “I suppose you were the best and worst of the American West. Our stories wouldn’t be much if you hadn’t been around, even if it was a short while.”

Kevin took the bottle, poured himself another shot, and then turned back down the trail, hurried, I assumed, by the approaching darkness. I followed closely and we got to the sidewalk and then down to his truck without incident, though he had given up on his paper cup and was tipping the bottle straight back and guzzling. I was hoping he did not intend to drive.

“You know, I read that Doc might have lived longer without the hot springs. A doctor was quoted in some newspaper feature saying the irony was that Doc came here to clear his lungs but the sulphury vapors from the hot water probably accelerated his end.”

Kevin ignored my history lesson.

The Hot Springs in Glenwood today

“I need you to do me a favor.” He was leaning with his back against the passenger door.

“Drive you back to the hotel, I would assume.”

“No, drive me out toward Basalt. I gotta pick something up.”

“You’re pretty drunk, man, and I don’t really have any business driving, either.”

“It’s important.”

“Can’t it wait?”

“No. I need it now.”

“You’re gonna have to tell me what it is to convince me to drive to Basalt.”

“It’s not that damn far.”

“I know, but what am I getting myself into?”

“Nothing. I just need to pick up some toot.”

“Toot? What the hell is…”

“Yeah, makes me feel better and I can work for days before I have to crash.”

I said nothing for a minute and looked at my friend but tried not to betray any judgment. I wondered what I might be getting myself into and saw a drug dealer’s shack with guns on the porch and cops cruising past in the dark.

“Sorry, man. Can’t do it, Kev. I just don’t care for the risk, and I don’t want to help you to hurt yourself any more than you already are.”

“Are you serious?” Kevin quickly stood and moved away from the truck. “Who do you think you are? You judging me? I hardly even know you.”

“Yeah, but I’m not going to do it, and I sure as hell hope you don’t get in your truck and try to drive, even back to the hotel.”

His answer was to simply turn away, walk around the front of the truck, sliding his hand across the hood to keep himself stable, opened the door, turned the ignition, and roared off in the direction of Basalt with a squeal of tires. The fact that he had clicked on the lights gave me some hope, but I saw red taillights swerving in the dusk as he opened the distance between us.

The next morning, I left for several days on a trip to Denver. When I returned, I called Kevin’s room several times during the day and into the evening. I went up to his door and knocked the next morning, hoping to catch him before he left for work, but he did not answer. A few days later I went to the front desk to ask the clerk if he had seen Kevin and was told he had checked out several days previously and left no forwarding address or phone. I was at least relieved that he had made it safely home from his mission to Basalt.

I searched his name on the Internet a few times through the recent years and found no trace of Kevin. The idea that he simply disappeared without word is still bothersome after more than forty years. I have a hard time seeing him as a grandfather, but I hope he found some more common sense and is still living a long and fulfilling life. If he did not, I prefer to think he is somewhere across a card table from Doc, playing an eternal game of faro, drinking expensive whiskey, and telling each other lies about their lives in the West.

That’s not a bad ending to any man’s story.

Thanks, buddy. I'd love to, but I'm no longer sure I can find an agent, much less a publisher. But it is a thought I have, as would be natural for a writer.

I’ll be your Huckleberry. Lord I love that scene so. But good to get some reality, even if it’s Kevin’s 😉. Another great story James. Good to read it as it always is. Life > politics sometimes, and certainly more interesting, generally.