(This newsletter aspires to offer information, insight, and maybe even entertainment. There will be personal experience included since I provide a point of view. But my focus is on this confounding state, its myths and realities. I will write about travel, literature, history, movies, politics, and just life its ownself under the Lone Star, and the broader influence of Texas beyond its borders.

It’s free to anyone who wants it, but those modest paid subscriptions, if you are inclined, can help fire the engines. Go ahead and be inclined. I’ll publish at least once a week, depending on interest, yours and mine. I will also post randomly with stories worth sharing and that are not part of the weekly newsletter).

“Don’t turn here into why you left there.” - Matthew McConaughey

The Austin Paradox

One of the sweetest memories I acquired from living in Austin since the 70s came from the iconic music venue the Armadillo World Headquarters. The number of people who can remember the music, and the beer-soaked carpet, is shrinking, but those of us who were there carry vivid images. We can hear B.B. King’s guitar and remember the goofy lyrics of Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen singing, “Mama Hated Diesels,” and the soft blanket of humid night air that made Austin feel safe and young.

One of my favorite performances of the many I got to experience was Harry Chapin’s. He came to the Armadillo a few years before the tragic accident that ended his life on the Long Island Freeway. I loved the lyrics to all his songs and knew them by heart from leaving his cassette in the player on my Dodge cargo van as I rambled around South Texas on weekends, running to the beach, or down to Mexico with my new bride. We got close to the stage for Chapin’s set at the ‘Dillo, I howled along with every word, and watched the singer’s son Josh, probably only six or seven years old, as he stood below his dad and rocked back and forth to his father’s music.

Local News Report on the Demise of the ‘Dillo

By now it has become some sort of clichéd talisman for long time Austinites to talk about the Armadillo as our connection to the glories of what once was in “our little town.” Maybe the end of the concert venue was made more acute for me because I was there the day the wrecking crews arrived and knocked down the clapboard walls to clear the lot for an apartment complex. I think there are many of us who consider that maybe a bit of our innocence got bulldozed that day, too.

Part 1 of a Special on the End of the ‘Dillo

Everything changes, of course, and often because of growth. I do not think, however, you can mark the moment the glacier began to move over Austin’s past with the destruction of the Armadillo. If there is a moment that divides the present from yesteryear in our town, I believe that is the day Matt Martinez agreed to sell his restaurant site on Cesar Chavez to the Southland Financial Corporation of Dallas to make way for a future Four Seasons hotel.

Matt and his wife Janie had captured the culinary hearts of thousands from within and without Austin with their food at Matt’s El Rancho, which started as a ten-table restaurant. Janie cooked, and Matt, a former Golden Gloves boxing champion, greeted everyone at the door with a smile and handshake. The guests were people like Willie Nelson, University of Texas football coach Darrel Royal, sportswriters like Dan Jenkins, and anyone who had heard the word about the food, which included President Lyndon Baines Johnson. Perhaps apocrypha, but LBJ is said to have dispatched a jet to Austin from Washington just to pick up enchiladas from Matt’s.

Even though the restaurant still exists and boasts 500 seats at its only location in South Austin, not much of the Austin that was around when Matt sold his land still abides. The Four Seasons Hotel sits on his former property, the Goddess of Liberty still stands atop the Texas capitol, and water moves through Lake Lady Bird, but, man, look about you and tell me what you recognize or still love. Yes, there remains much to make our city attractive to the 180 people who are said to be arriving daily, but we might be destroying the culture that initially drew us all to the “city of the violet crown.”

But before I take a limited inventory of the change and try to understand where we are going, a joke. I wrote this trite little line or two because I grew weary of hearing long time Austin residents talk about cool places from the past: How many Austinites does it take to change a light bulb? The answer, of course, is 100. One person to change the bulb, and 99 to talk about how great the old bulb was and what wonderful light it gave off.

Hilariously, for a while, we had a local cultural caste system around town. The more of old Austin you had experienced, the cooler you became.

“Dood, do you even know what Liberty Lunch was?”

“No, but I used to eat at Las Manitas when I first got to town.”

“Sit down, outlander!”

Liberty Lunch was just the other side of Congress from where Matt and Janie’s little restaurant and house had stood. The structure, old brick and heaving beams, almost seemed to sag in its Second Street location. For a while, there was no roof on the joint, but that may have served to send the music rockin’ on the water of what was then known as Town Lake. Too many soon-to-be-famous bands to mention played the strange little venue that brought together rednecks and hippies and frat rats and business types to drink longnecks and listen to emerging talents like Nirvana and Dave Matthews, Joe Ely, Beto y los Fairlanes, the Smashing Pumpkins, and the beat goes on.

When Liberty Lunch closed its doors in July of 1999, old Austin had drawn its last deep breath. The waterfront property, which was increasing in value almost by the minute, was too pricey to leave undeveloped. The city owned the site and leased it to Computer Sciences Corporation, which has served, inconsistently, as an accelerant of Austin’s high-tech profile. The “weirdness” the town has tried to keep has been slipping quietly away every time another band unplugs an amp. The incontrovertible fact is that Austin never really was all that “weird,” except for once a year on Eyeore’s birthday party, a distinguished gathering of unique individuals in Pease Park. I think of it as a kind of low-budget version of Burning Man.

If we had any weirdness, it came from the music spilling out onto the sidewalks from bars, restaurants, and stages, all over downtown. You could walk down almost any street and step into an unmarked façade and encounter musicians like Jerry Jeff Walker or Stevie Ray Vaughn or Guy Clark or Marcia Ball, and have a pitcher of beer for $1.75 while you wondered how all this talent ended up in Austin. Willie, of course, had much to do with that when he decamped Nashville and came home to be followed by a lot of other musicians. There was also a movement in radio I have referred to as the Great Progressive Country Music Scare, which for a while threatened to turn Nashville’s boys on 16th Avenue into insurance salesman. Instead, progressive country introduced Kristofferson and Waylon and Merle and, later, Townes van Zandt to a wider audience and evolved into Outlaw Country.

But radio has almost been replaced by Spotify and Pandora and Waylon and Merle, among many others, have “left the building.” Whatever Austin once was it no longer is and shall never be again. We used to be a town that sustained a yodeler as a businessman and restauranteur, who introduced Janis Joplin to a bigger audience. Kenneth Threadgill, were he still around, would likely be scratching his head over what has happened to his namesake restaurants and music venues. His torch bearer, Eddie Wilson, who founded the Armadillo and took over Threadgill’s operations, could not keep the places profitable because high property taxes and an increase in competitive culinary options for Austinites.

Today, the fastest growing city in America is struggling to figure itself out, and, not really doing that good of a job at it. Are we still weird? A live music venue? The Silicon Hills? A playground for the wealthy?

There is always some kind of existential crisis that comes with growth. The gains and losses are not balanced. Austin’s transformation, however, is confounding in the extreme, and, in some cases, even heart-rending. The people being drawn here from California and New York and the Midwest cannot measure the loss of something they never knew existed. They see the glassine towers shimmering in the evening sun, feel the cool, clear water of Barton Springs, have a Mexican Martini at the Cedar Door, and convince themselves they have landed in Shangri-La with a sales tax. Austin’s reputation that drew newcomers is disappearing beneath the foundations of the high-rises the neophytes need for places to live.

Forgive my curmudgeonly attitude but I have previously, in my youth, lived through this process. Although I have spent my entire adult life in Texas, I was born, raised, and educated in Michigan. My parents had gone north from the cotton patches of Mississippi to get a job in one of the car factories, which was what thousands of other Americans were doing as they searched for the future in a post-World War II economy. My parents’ options were limited with 8th and 10th grade educations, but they saved their money from their last season of growing cotton and bought bus tickets to Flint, Michigan, where they knew not a soul. Nonetheless, they were befriended by an elderly lady who saw them wandering aimlessly among the luggage passengers and she gave them a place to stay with the two kids while they tried to get hired.

Eventually, Daddy got employed as a laborer at the Buick Motor Division and Ma carried open-faced sandwiches and burgers in a restaurant that catered to truckers and factory workers. Their American dream probably fell somewhat short of their aspirations, but they were no longer chopping cotton and there was a steady, if modest, supply of money. They were surrounded, however, by plenty. The polished steel rolling off the assembly lines, though it was nothing they could ever afford, was changing the country as the new cars were shipped to dealers and ended up cruising Colorado Boulevard and the Pacific Coast Highway and redefining what we all thought were our own possibilities.

1957 Ford Mustang Assembly Line

The parallels between Flint, Michigan in the 50s and 60s and Austin, Texas in the 90s, aughts, and teens, are curiously ornate and hard to avoid. I am not implying Austin will be plagued with lead-lined water pipes like Flint, but my hometown was also overrun with Californians and Southerners, all come north for work. Detroit, and the Tri-Cities of Flint, Saginaw, and Bay City, had become the de-facto center of post war technological advancement and, yes, even the arts. We gave the world automatic transmissions, power windows, four-barrel carburetors and Motown. There were not many transistor radios anywhere in the country that were without stations tuned to the songs of Smokey Robinson and the Miracles and the Supremes and Aretha Franklin and all the other talent emanating from the Great Lake State. Probably, the happiest people in all the land were mechanical engineers who loved music, working on new ideas to improve automobiles while listening to songs by Marvin Gaye and the Four Tops.

There were, as there always is, significant downsides to this progress. One of the greatest trans-migrations in American history created disaffected souls, away from families, stuck in dark, loud factories, thinking about their next drink, or just walking out the door and going home. The Southern and Western diaspora in the cold, cold North took a generation to completely adjust to their new homes in the Midwest, and they had homes, not just sharecropper shacks sitting in a sea of cotton plant green. Farmers sold land to subdivide and turn into neighborhoods and the VA provided one and two percent mortgages to those who had served in the military. My father borrowed $500 from his sister for a down payment on a new construction home that cost $10,400 and got 832 square feet for his wife and what was soon to be six children.

He never stopped being homesick, though, like millions of others who had left behind their childhood families to find jobs and lives away from cotton rows and hard labor in the sun. America never took stock of the impact the migration had on individuals, but it was painful and an ache that many quietly endured. No artist captured the moment more succinctly than musician Bobby Bare with his song “Detroit City.” I do not think Bare ever played his hit tune without heartache on his face, which was readily apparent even in this 1964 performance in Oslo, Norway.

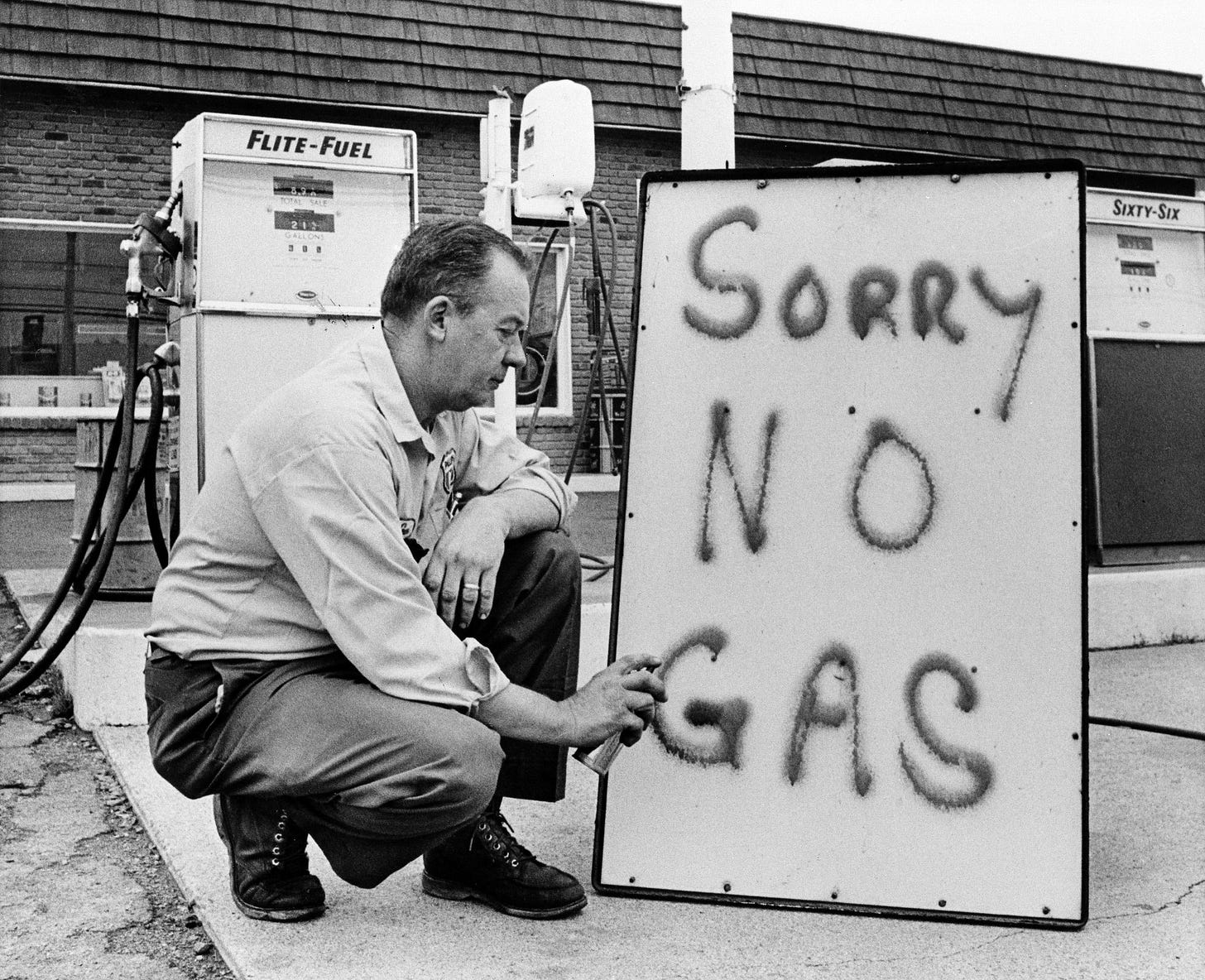

It did not take long for the V-8 version of the American dream to get tattered and ragged around the edges. The 1973 Arab oil embargo forced US motorists to reconsider their love of muscle cars when the cost of a gallon of regular gasoline rose to 55 cents and the price of a barrel of oil quadrupled from $3 dollars to around $12. The OPECkers were making retaliatory moves against the US for constantly resupplying the Israelis during the Yom Kippur War. The stock market subsequently crashed and a lot of brightly painted, big block, Detroit iron spent its time getting polished as garage jewelry because driving was no longer very affordable.

Instead of making smaller cars, though, the Big Three auto companies pressured Washington to manage prices with OPEC and by federal fiat, which did not work. The Japanese, meanwhile, saw an opening in the American market and began to offer small, four-cylinder vehicles that were far more gas efficient than the Chevy Malibus and Ford Thunderbirds. The price of a gallon of gasoline never returned to pre-embargo prices but motorists were slow to abandon their big wheels. Nonetheless, Japan discovered a growing enthusiasm for compact cars and built a demand in the American market while GM and Ford kept churning out massive machines for Americans, who, as always, expected things to get better even when all the indications were that the ground was moving beneath our feet.

Layoffs followed. US carmakers did not adapt quickly enough to the changing market dynamics. Families returned to the South. The clean new neighborhoods of matchbox houses with a single cedar tree in the yard and a flower box beneath a picture window, began to show for sale signs and foreclosure notices. The downward side of the Bell Curve of growth had us all sliding toward un-payable bills, government cheese and powdered milk, domestic and racial violence, and all the societal ills that follow an economic rupture. Detroit had no choice but to reconfigure, and did, but far too late to minimize economic and emotional pain for its workers.

I am not suggesting Austin faces such challenges, but there are lessons to take from any growth and downturn cycles. Real estate prices will likely eventually affect in-migration to Central Texas, and an outdated tax code that puts a heavy burden on homeowners to subsidize tax abatements for companies like Tesla and Apple and Samsung will have to be rewritten before markets collapse or people stop coming to town. We also need to take an honest full measure of what’s being lost and what’s being gained. You cannot simply knock down and then build up anew and think that process and its outcomes are always positive. It has become almost axiomatic that we are destroying the things that made people want to move to Austin by building more places to serve the people who moved here, and that might be the only bit of “weirdness” we have left.

People will keep coming, though, and they will not miss what they did not know. If they are arriving from California, the real estate costs will not seem so prohibitive, and they will find the places that are defining the new Austin, an emerging culinary capital and a recovering “Live Music Capital of the World.”

And most of them will say things are great.

Growth needs to have more value and purpose than just profits, but even the Armadillo was about making money. I remember when the music venue closed and we were shooting video before the wrecking ball swung and someone had climbed up on the roof and left a cryptic, hand-sprayed paint message on the sign, reminding us to be careful of the future, what we had been, and what we might become.

“Thank you, Austin, Tejas, wherever you went.”

The Variant Next Door

The political disease stalking Texas is as deadly as the Covid virus. Patient One is Governor Greg Abbott, who is proliferating ignorance and allowing the real virus to kill innocents, which will soon include an increasingly large number of children returning to school without masks. The only location where Abbot appears concerned about the Delta variant of the virus is on the border. Because he needs an enemy, he has chosen the sick, homeless, hungry, and poor to be his scapegoat.

Nothing seems to move this man’s heart or politics. While the CDC says masks and vaccinations are the only way to stop the spread of the more deadly Delta variant, Abbott issues an executive order telling schools, counties, and state agencies they cannot mandate masks. Anyone who may have been exposed to the variant, contracted it, or is sitting in a government building or school next to someone carrying the virus, is now at risk because Greg Abbott wants to appeal to conservatives who do not like government orders.

And lives will be sacrificed on the altar of his presidential political ambitions.

Hospitals across Texas are putting out “No vacancy” signs for ICU patients, and, in many cases, having to delay any other types of treatment for patients because of contagion risks. As I write this, an 11-month-old baby girl was airlifted from Houston to a hospital north of Austin because there were no ICU treatment facilities left in Harris County. An increasing number of children under the age of 12, who are not eligible for the vaccine, are becoming infected because Abbott has told their parents and every other person in Texas that they do not need to wear a mask if they do not desire to cover their noses and mouths. In a news conference, the governor said the state had moved past “mask mandates and into the era of personal responsibility.”

Abbott is only concerned with the virus in immigrant populations, and not because he worries about their health. He is using potential infections to increase his crackdown and raise money to build his silly backyard wall and arrest people for trespassing so he can throw them in prisons, which will turn them into Covid hot spots while they wait for a hearing. Migrants getting sick behind high walls and even dying is of no matter to the man. Providing a political foil is their most important role. Unsurprisingly, possibly the most widely vaccinated populations are among people living along the border. Abbott is demonizing the Mexican and US frontier with Covid fears but this CDC survey from the New York Times shows well above average rates of jabs along the Rio Grande.

Abbott’s own personal responsibility is missing, though. He has done nothing to help rural communities where the lowest vaccination rates are recorded because of, in large part, conservative politics that Abbott and others have spread to suggest the virus is not that deadly and the government ought not to be making your health decisions. Even before the virus struck, rural health care in Texas was on the ropes. Small town hospitals were declaring bankruptcy and even closing because patients could not cover their bills and Abbott refused to expand Medicaid, which would have a huge financial impact on rural health care.

The only help rural hospitals in Texas have received came from the Biden administration and a grant of $29 million to help with Covid mitigation and vaccinations. When hospitals began to ask Texas to send money to help hire nurses and additional staff for the pandemic, they received a letter, authorized by the governor, telling them to pay for it themselves and use their city’s stimulus money, if they still had any.

Not much stimulus cash went to Texas rural areas. The tragedy Abbott has teed up in rural parts of the state began with his ongoing refusal to expand Medicaid, which would help hospitals pay for treatment and provide coverage for much of the state’s uninsured population of five million, which includes almost a million children. Texas taxpayers have already sent about $22 billion dollars to the federal government to pay for Medicaid during the Abbott administration’s years, but instead of that money returning to help this state, it gets distributed to state’s that have Medicaid.

Abbott is also hardening the economic and education divides that threaten lives and the economy in Texas. A stunning survey by the New York Times reveals the effect the pandemic has had on low income and rural areas in terms of education. The paper studied two-thirds of US schools and discovered about a million economically marginalized children did not even show up for kindergarten and will eventually begin their school lives educationally handicapped.

The tragicomic nature of the virus and politics in Texas is that rural areas are supporting Abbott and his policies. Even as he puts their lives at risk, the governor gets overwhelming backing from the unvaccinated and the conservatives outside the metro areas and especially in West Texas. It ought not be too difficult for even the marginally educated to believe in science. Probably 99 percent of Texans and others refusing the vaccine got various types of vaccinations like polio, chickenpox, measles, mumps, rubella, and, if they went off to college, a meningitis shot, because most colleges and universities now require the protection for incoming freshmen.

Governor Abbott is unmoved. Do what you want. Wear a mask, or don’t. He doesn’t give a jolly good goddamn about anyone in this state who is not a part of his political base, and if some of them in rural areas must be sacrificed to make his point, that’s a price he is willing to pay with their blood. Abbott wants a broader national message that he is the whack job who can replace Trump.

And if innocent people must die to achieve his ambitions, that’s just the cost of doing political business.

This week's TttW gives the readers two excellent reasons why it's time to leave our Lone Star State.

Jim, As always loved your most recent essays, even though it makes me feel a little guilty about moving into your neighborhood ... (Am I part of the problem?). Check the cut line on the pic of the Ford Mustang Assembly line. I assume 1957 is a typo...Should that be 1967?

(https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/ford-mustang-debuts-at-worlds-fair. Just picking nits... doesn't change your point.