"Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depth of your heart; confess to yourself you would have to die if you were forbidden to write." ― Rainer Maria Rilke

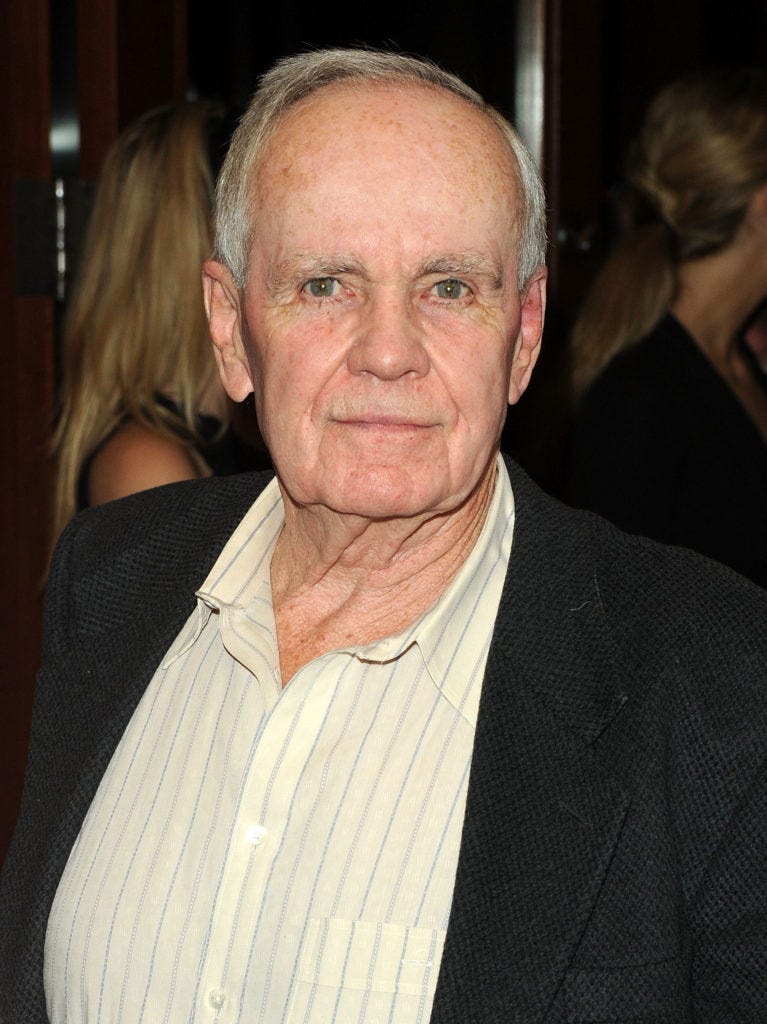

Cormac McCarthy has died of natural causes at his home in Santa Fe. His work is a literature that looks at hard truths about humanity, who and what we are, and even worse, what we do. His sentences, I always thought, felt as out of control as the subjects and characters of his stories. I don’t think American literature has had such a voice since Faulkner, whose work was not nearly as accessible in his time. I think I’ve read McCarthy’s every word. Like every great author, he never did more than write. An odd job here and there to buy food, but his job was to write.

I like to write, too. Many of us suffer the affliction. More accurately, though, I need to write. I must. The craft is central to who I am and has been since I first began to read. Stories fascinated me. I wanted to create my own. And share them with anyone interested. Even those who weren’t. I hoped to have people read my words and talk about my ideas or characters.

I don’t know where this came from, but it has always been in me. In elementary school, when Mrs. Hagemeister assigned a story to be read, I was finished on the bus home. I lay awake at night hoping she might call on me to read a section aloud to the class. I wondered how that might feel if it were my words. Was there a possibility to earn money writing stories?

There were other things I might have been. And I have become a few of those. Nothing has been as constant, though, as my perception of myself as a writer. I have even tried to stop, frustrated at my ability or the silly notion my words might have value or purpose. My desk drawers used to be filled with printouts of draft novels and screenplays that lay unrevised. They now populate little blue folders on my computer desktop. More are being created in the moments between paid work and travel and family commitments. There is always time to write. On an airplane tray table. In a roadside motel. At a friend’s house. The back seat of a car. In a tent while it is raining. If it’s in you, it’s got to come out.

Many of my journalist friends, in fact, almost all stopped writing when they quit the business. I did not. They wonder what is wrong with me. Sometimes, I do, too. But I am compelled to write and express ideas and images and narratives. My friends always saw this as a job. I view it as a joy, though I’d like to earn a bit more in the process.

Writing, of course, is a practiced and studied craft that requires an output of product on a regular basis to achieve a final vision. Good writing has never been the exhibition of a gift but is always the result of regular, hard work. William Styron was quoted more than a few times claiming that he wrote only a paragraph a day because it was the singular technique that he knew for perfecting his vision. This explains, perhaps, why it took him six years to complete his epic The Confessions of Nat Turner.

My favorite story about motivation for writing comes from a little cafeteria at the foot of the Franklin Mountains in the desert of West Texas. The late Cormac McCarthy, the peripatetic genius, moved to El Paso from Tennessee to concentrate his work on the American West. In the UK, he was already widely known as a man of great talent for his books like Blood Meridian, Child of God, Sutree, The Orchard Keeper, and others, but in the U.S. his work sold only to a core group of readers who appreciated his rich, ornate prose and vivid descriptions. His publisher said McCarthy’s books never sold more than 5000 copies. Then, however, he won the National Book Award for All the Pretty Horses.

I admired and resented McCarthy for his depiction of the American West. I had previously fallen in my youth for the idyllic imagery of good guys and bad guys and the argued necessities of Manifest Destiny, though I abhorred the brutalities. The truth of our history was bloody, of course, and McCarthy had captured the scalping of indigenous peoples for $1.50 for each head of hair, and the random killing of anyone who might be in the way of a gunman’s indiscretion. His characters were based on real humans roaming the deserts and having their way with pistols and rifles and guns in a lawless land. I have never been able to comprehend the source of his stories and his ability to render reality in such graphic form. His vision seems to originate in some unknowable source.

But I wanted to know him.

Famous for being reclusive, McCarthy never spoke with journalists; except once in a 1992 interview with the New York Times. The fact that he was finally ascendant in his native country, however, prompted an editor of a London newspaper to dispatch a reporter to Texas to seek a more contemporary interview and do a profile of the author. I’d had a slightly less ambitious goal for many years as a fan of his books. Blood Meridian had changed my romantic view of U.S. western history and I devoured every word McCarthy had ever committed to narrative. I just wanted to see his face and determine if there were a way to pick out greatness in a crowd, to see if it was betrayed by the eyes or the lines across his brow or the muscles of a smile.

As a TV news correspondent, I frequently traveled to El Paso to report on various issues and had heard McCarthy hung out at a particular pool hall at the end of his writing day and frequently took his lunch alone at a cafeteria on Mesa Avenue. As hard as it was for me to see him sitting at a table for one eating square fish or the LuAnn Platter, I still stuck my head into the cafeteria whenever I got a chance, hoping to see the great man in physical form. I never did and I considered that chasing him down at his neighborhood pool hall was a bit too much of an invasion, though it took great will power to keep my distance. I sometimes wish I had not.

The British reporter, who apparently hung out at the cafeteria long enough to see McCarthy, is said to have walked up to the author’s table to request an interview. I don’t know if this story is apocryphal, but it resonates with a certain truth. Although the correspondent was polite and sought forgiveness for the interruption, McCarthy was non-responsive. The reporter, as reporters will, persisted until McCarthy told him, “I don’t do interviews.” Undaunted, this journalist explained how he had traveled across an ocean and spent thousands of dollars to try to find McCarthy and that his editor was pressuring him to deliver. The author was unmoved and did not speak. Hell, I can see him slouching there and scooping up his peas and moving forkfuls of his square fish into the pile of tartar on his plate, acting as if the determined newspaperman were not even alive, much less standing next to his table.

The Englishman was silent until he came up with a new idea. Perhaps, he assumed, McCarthy would at least offer some advice on the topic of writing. According to the story I was told by a friend of McCarthy’s, the reporter begged for words of wisdom on the craft. The great scribe remained impassive and silent through repeated requests.

“Mr. McCarthy,” the journalist pleaded, “can’t you at least just give me some advice on writing? People would love to hear anything you have to say about it.”

McCarthy’s face was impassive but there was a decision moving across his weathered countenance. He was willing to speak, though he didn’t put down his fork or stop eating. His rendered insight, however, ought to be hanging over the desk of every wannabe author or columnist or novelist manque’.

“As far as writing goes,” McCarthy said without lifting his chin, “If you don’t have to write, then don’t.”

And there it was, wisdom winnowed down from the cosmos, passed through the genetic code of literary masters and artists, boiled in the blood of frustration, bred from the nonsensical optimism that there is reward, monetary, emotional, or intellectual, in the desire to write. There ain’t, McCarthy was explaining in as sparse a language as he could muster. There just ain’t. Writing is a primal urge for some souls and a craft at which to be clever for the merely artistic. Odds of recognition or financial success are long.

There are no masters in writing but there are many slaves. The truth that had traveled through the ages passed over the tartar sauce on the wise man’s breath and rose with a snake-like hiss to the reporter who busily scratched the words onto blue lines and left as if he’d discovered golden booty. Perhaps, he had.

“If you don’t have to write, then don’t.”

Nobody has ever said anything more illuminating about writing. You know if you must write. You arise every day with it simmering in your brain’s convolutions. If you don’t, then go find something to do that is more lucrative or emotionally gratifying, and that’s a pretty long list of endeavors.

McCarthy left Texas and hied on up to Santa Fe, a transition easy to respect. The long light there is perfect for artists, regardless of the media in which they labor. His two new books, published last fall, are as confounding as almost every other story he has told. McCarthy tried to understand the mysteries of existence but he left behind more than a few he had created with his work.

It’s just words, of course. But they are all we have. And they are the only thing that has ever changed the world, or even begin to help us understand it.

Thanks for the thoughts Jim. His writing is brutal and beautiful. I love it. The late Wade Goodman had a very nice piece on him that NPR played in full (I believe) this afternoon.

I just googled it. Apparently, lots of writers have said various versions of blood on the forehead!!!! Nobody knows for sure.