Caught by the Chill

Part One

(Exactly twenty years ago this week, the U.S. was completing the assembly of men, women, and combat materiel along the Iraqi frontier with Kuwait. Based on cooked intelligence, America was about to launch an invasion to overthrow Saddam Hussein. The war had been justified by claiming the dictator was on the verge of making nuclear weapons and had been connected to the 911 terrorists. Neither assertions were true, and the Bush administration was aware of the falsehoods.

What follows here is the story of a young man from Nevada, a Marine, who by all witness accounts, was probably the war’s first American casualty. This narrative is based upon reporting, interviewing, and writing I did at the time, and much of it is included in my second book, “Bush’s War for Reelection.” The title of this two part story is taken from Gordon Lightfoot’s song, “The Patriot’s Dream,” which includes the verse, “Let’s drink to the men who got caught by the chill, of the patriotic fever and the cold steel that kills.” Part two is being dispatched at the same time as this first section.

As always, I appreciate your support for my work, and I ask you to share, and subscribe, free or paid. Every new regular reader keeps me inspired. - JM)

“To save your world you asked this man to die; Would this man, could he see you now, ask why?” - W. H. Auden

In his comfortable home, set on a ridge line above Tonopah, a surprise awaited Sheriff Wade Lieseke as he returned from his duties in Pahrump, Nevada. Three days of the week, Lieseke lived out of a motel room in Pahrump. Though his home was in Tonopah, on the other side of Nye County, Pahrump was the biggest city in the nation’s second largest county. To do his job, the sheriff needed to spend a lot of time away from his family. All 18,000 square miles of Nye County, the endless hazy distances of the Great Basin Desert, were a part of his law enforcement jurisdiction.

On the right hand wall as he entered the house on this evening, a shadow box had been hung. In perfect rows, his medals for military service in Vietnam had been placed behind glass, centered on a folded American flag. Lieseke had lost track of the location of his combat decorations. He wasn’t ashamed of his service, but it wasn’t exactly a time that had given him great happiness, either. The medals had been put away for a reason. Soldiers don’t like to be reminded of war.

“I looked at that thing on the wall,” he said. “And I knew right away it was Fred. You could just tell he had done it by the perfect rows he had hung the medals in. It was all just so precise, so Fred.”

Lieseke’s adopted son, Fred Pokorney Jr., had come home from the Marines for a few days. When he arrived, he had asked Susy Lieseke where he might find Wade’s medals from Vietnam.

“Where’d you get those?” Lieseke asked Pokorney.

“Suzy and I dug them out.”

“Why? I had put those away. I never want to think about them any more.”

“I know,” Pokorney said. But that’s where they need to be. Right there where people can see them. You need to be proud.”

Wade Lieseke looked at the commendations he had received as a door gunner on an attack helicopter. He had served in four of the war’s major campaigns, and had been decorated with the National Service Medal, Vietnam Service, Vietnam Campaign, the Army Commendation, and Air Medal, the Purple Heart, and the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with a Palm Leaf bestowed by the government of South Vietnam. Lieseke knew something of war. Hundreds of Viet Cong had died from his accuracy during fourteen months of flying combat missions. War was not something Wade Lieseke celebrated. He hated it as only a soldier can.

But he was moved by his son’s thoughtfulness.

“That’s pretty nice,” he told Pokorney. “I appreciate you thinking of me like that.”

Pokorney smiled. “Yeah, there’s just one thing wrong with it.”

“Oh? What’s that?”

“That.”

Pokorney pointed his finger at the U.S. Army insignia near the top of the shadow box. He had positioned it above a shoulder patch, which he had given to Lieseke, designating the sheriff’s military unit; “282nd Assault, Alley Cats Helicopter Company.”

“What’s wrong with the Army insignia?” Lieseke asked.

“It oughta be the Marines,” Pokorney explained. “You should have been a Marine because they’re the best.”

Fred Pokorney Jr. did not come into the world as Wade Lieseke’s son. Lieseke, whose physical presence in a room demands almost most as much attention as the six foot, seven inch Pokorney’s, first met the future Marine while Fred was dating Lieseke’s daughter, Angie. During his high school years, Fred Pokorney had come to Tonopah with his father. They were living with Fred’s aunt, while Fred Pokorney Sr., worked construction in the mining town. When his aunt died, Fred’s father decided to look elsewhere for work. The younger Pokorney, however, did not want to leave Tonopah.

Wade Lieseke invited the young man to come live with his family.

“Sure, you think about what you are doing when the kid is dating your daughter,” Lieseke said. “But with Fred, that just wasn’t an issue. You just met the kid and you knew he was different, very special. You were in the presence of someone outstanding, and you knew it. Him dating Angie was never a worry. We had our discussions. He knew the kind of behavior I expected. And that’s the way he acted. I never had the slightest reason not to trust Fred.”

In Tonopah, Fred Pokorney was noticeable. Tall, with green eyes and dark hair, he was a natural athlete. Classmates say he never struggled to fit in with his peers, and became a leader, even though he was quiet, not what many students considered outgoing. On the football team, Pokorney was a big target as a receiver for the quarterback, and a daunting obstacle for running backs to get around when he played defensive end. A teammate said Fred was “always good for at least one touchdown a game.” Basketball, though, appeared to fit more closely his physical skills. Whenever the Tonopah Muckers competed, Fred Pokorney always seemed to be in the middle, underneath the basket, clearing out rebounds or dropping in two pointers. During off-season, he spent his time in the high school gymnasium, lifting weights, trying to “put on size” to help attract the interest of college recruiters.

Rarely, if ever, did Fred Pokorney speak of his birth parents. He had told Suzy Lieseke that the last time he saw his mother was at age six, after she had left him abandoned in a shopping mall near Lake Tahoe, and politice turned him over to the custody of his biological father. Many people in Tonopah assumed Pokorney’s parents were Wade and Suzy Lieseke, even though Fred had lived with them as foster parents. The Lieseke’s never formally applied to adopt Fred because, according to Wade, he never felt he needed a “piece of paper to make him my son.”

“That’s just who he was,” Lieseke said. “He was my son.”

He was born, however, to a construction worked named Fred Pokorney Sr., who moved around the American West, and his first wife. Around the time he was entering kindergarten, Fred Pokorney’s parents divorced. No one in Tonopah had ever heard him speak of his mother.

“We always just assumed Fred’s birth mother was dead,” Suzy Lieseke said. “He never once mentioned her to us, and we didn’t pry.”

Whatever his childhood hardships were, Pokorney was reluctant to share the experiences even with his closest of friends, and he did not let the past burden his teenage years. Fred Pokorney excelled in sports, was a fine student, and worked two jobs, at the Mizpah Hotel, and an open pit mine. He went about the business of building his own life.

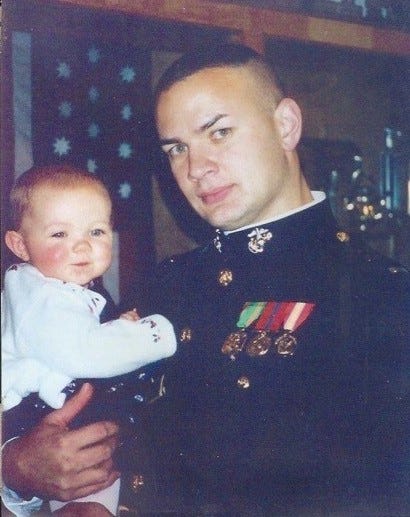

The Marine and his Little Girl, Taylor

“He was a pretty independent guy,” said former high school teammate Mike Grigg. “Rather than sitting and pissing and moaning about it, he was working two jobs. He didn’t expect anyone to support him, even in high school. What happened, happened, and he seemed more than confident he could take care of himself.”

Grigg, who is a Nevada State Trooper in Tonopah, came across Pokorney during Marine boot camp. They spoke only briefly, but long enough for Grigg to realize Fred Pokorney was driven into the Marines by the same focus he’d had in high school.

“He was far beyond my maturity level when I was going to school,” he said. “Most kids tend to be carefree and not pay any attention to the kind of things Fred was dealing with, like work and responsibility. He was down to earth and hardworking. His work ethic was outstanding.”

No one admired Fred Pokorney’s determination more than Wade Lieseke. Until he was shot and critically wounded by a Utah prison escapee, the sheriff had not missed a single game in which Fred played football or basketball. The one contest he was unable to attend was the East-West Sertoma Classic in Reno, an All-Star game for high school seniors put together by the Sertoma club of Reno. In a Las Vegas hospital, Lieseke lay recovering from the damage done by a bullet, a ripped diaphragm, torn lung, and ruptured spleen. When he got out of his patrol car, the flash of the convict’s gun prompted Wade Lieseke’s adrenalin to stir in his combat instincts, and he fire several rounds, killing his attacker. The 1989 incident was later featured on a national prime time television broadcast.

Many weeks later, after he had been released from the hospital, one of the people he depended on the most while his wife Suzy was at work, turned out to be Fred. Pokorney spent his first summer out of high school in Tonopah saving money to help pay for his freshman year in college and assisting Wade Lieseke in his recovery. Pokorney’s goal of attending college and playing basketball had been achieved. After an injury during his freshman year, however, Pokorney did not return to the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. He stayed in Tonopah, working construction and the silver mines.

Wade Lieseke noticed Fred had started talking about joining the military, in particular, the Marines.

“I just kept trying to talk him out of it,” Lieseke said. “I wish to hell I’d tried harder. I told him if he wanted to join up he should join the Air Force or the Navy, not the Army, and surely not the Marines. It’s just too damned dangerous.”

As he spoke, Wade Lieseke and I were having breakfast at a small casino on the north side of Tonopah. The road outside, Veterans’ Memorial Highway, sloped north toward Reno, and then down from Tonopah’s altitude of 6100 feet. Behind the casino’s restaurant, on a small plateau, desert wind blew dust across Logan Field, a modest patch of green where Fred Pokorney had run to glory in high school football. Above the conversational clatter of the restaurant, the ping and rattle of slot machines were heard, even during the early morning hours. The air in the lobby was thick with the putrid tang of cigarettes and alcohol, as if small town desperation had become a stench. Lieseke’s big hands curled around his coffee cup, and he looked out the window as he spoke.

“I said, ‘Fred, my problem is that the Marines are always the first ones in there,’ and he said, ‘That is the tradition and the history.’ And I told him, ‘You also have the first opportunity to get killed.’”

Pokorney’s determination served him well when he joined the Marines. On visits to Tonopah, Wade Lieseke became convinced that the young man, who had brought additional, unexpected happines into his home, was certain to become the first four-star Marine general who had not graduated from Annapolis. Fred Pokorney loved being a Marine. He was part of an organization that appreciated and understood his kind of personal strength, the independence and will that men need to do great things. Fred had cultivated these characteristics within himself, and nothing pleased him more than being around people who valued what he had created.

He was home.

After commissioning as an officer, he was stationed at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Neither he, nor his wife Chelle, had ever been to the East. And once they had settled into the little beige house near the base, their first excursion to explore the East Coast was a trip for a Memorial Day visit to Arlington National Cemetery. Fred had always had a desire to stand in the sacred spot where American soldiers lay in honor. Chelle’s grandfather, who had served in World War II, was buried in Arlington, and they wanted to see his grave and offer their respects.

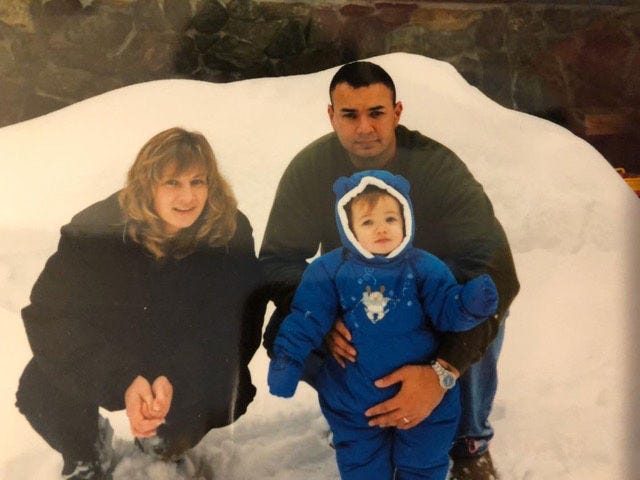

The Pokorney Family, Fred, Chelle, and Taylor

May 28, 2001, was also the first day for new President George W. Bush to deliver Memorial Day remarks at the national cemetery. After laying a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknowns, the president addressed a crowd spread beyond the seating capacity, standing among the tombstones and markers of the dead, listening, as their president tried to convey a context for the loss and sacrifice signified by the rows of honored dead filling the hills along the Potomac River. Out of uniform that day, Fred Pokorney was erect, his chin up above the crowd, as his commander-in-chief spoke.

“It is not in our nature to seek out wars and conflicts,” President Bush said. “But whenever they have come, when adversaries have left us no alternative, American men and women have stood ready to take the risks and to pay the ultimate price. People of the same caliber and the same character today fill the ranks of the Armed Forces of the United Sates. Any foe who might ever challenge our national resolve would be repeating the grave errors of defeated enemies.”

Undoubtedly, Fred Pokorney believed his president was talking to him. He was ready. He loved what he was doing. Serving his country in the Marines was the greatest job anyone could ever have. Fred trusted his president. He knew if he ever got orders to go into combat, it was because America was at risk, and he was willing to put his own life up to protect his country. If a Marine cannot trust in his commander-in-chief, he cannot fight in combat. Fred Pokorney believed in America; its principles, its leadership, its unrelenting truths. And he had just heard the president make a solemn vow that America was not going to be seeking out any wars or conflicts. If war came, it was certain to be the result of another nation’s aggression.

After the ceremony, Fred and Chelle lingered among the veterans. Many were wearing their combat decorations; gray and changed by death they had seen, the soldiers were, nonetheless, proud of their service. They had done what their country said needed to be done for freedom. Fred Pokorney spoke with many of the veterans. Hearing their stories made him feel a kinship, a connection to something holy. As he walked among the monuments, stood before the gravestones, and listened to the old soldiers, Fred Pokorney felt as though he were among his own kind.

“I want to be buried here someday,” he told Chelle. “It’s important. And you can be buried on top of me.”

After the holiday, back at the base in North Carolina, life for the Pokorneys settled into the daily rituals of work and household. On September 11, 2001, however, Fred, Chelle, and Taylor’s days together began to grow tense. America had been attacked, and Fred was a Marine. The consequences of those two facts were obvious, and needed no discussion in the Pokorney house. Months passed, and they heard the talk from Washington about Iraq, and aluminum tubes to build a reactor. Eventually, there was a report in the presidents State of the Union speech that Saddam Hussein had tried to acquire uranium from an African country. Even when they attempted to avoid the newspapers and television newscasts, the still heard about Iraq giving assistance to terrorists, maybe even some of the those who had attacked the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. The Pokorneys did not dissect the news. They simply knew what it all meant to Fred.

“We aren’t real political people,” Chelle Pokorney said. “Fred was just doing his duty. I do wish the country had agreed more going into it. I heard about most of this from my husband. Those people needed help, I guess. And we were there for that. I just hope they get whatever it was they wanted from us, freedom or whatever it was.”

Back in Tonopah, however, the rhetoric of the war was making Wade Lieseke sick with anger. Iraq looked like Vietnam without the trees. Americans would go in, fight and die, and then, ultimately, leave. Iraq was likely, in Lieseke’s estimation, to return to the mess it was before the United States invaded. He’d seen it in Vietnam. Lieseke wasn’t political as a young man, either. When the government said it needed soliders to help stop the spread of communism, Wade Lieseke believed in the cause.

“What I know now is that it was all a lie,” he said. “I mean, if you’re gonna do that, then do it. We got a lot of guys killed, almost 60,000 and I’m counting the POWs and MIAs that were never heard from. Whether you wanna believe or not they’re gone. That’s over 60,000 killed.”

Lieseke has scars on his body from wounds received in Vietnam, and there are others in his head that no one can see but him. He admits to being dark, too often depressed, thirty-three years after leaving Vietnam. There are memories he’d rather not have, the kind of experiences he hoped Fred would be able to avoid as a Marine. The experts call it post-traumatic stress disorder. Wade knows what he is dealing with, though, and often, it is just anger over the lies that sent him to war.

“If we are gonna let the place fall to communists, why in the hell didn’t we do that in the first place?” he asked. “Why did all those U.S. soldiers die? After all these years, what really was the mission? What did you witness all this death and destruction for? Why did you become part of this death and destruction? If nothing was gonna change?”

Pretending that attacking Iraq was going to reduce the terrorist threat was just another government deception, as far as Wade Lieseke was concerned. More kids were going to be killed. Nothing was going to be accomplished. The president just needed a war to distract from all his other problems, and Iraq had lots of oil. Washington leaders always made choices based on factors that had nothing to do with the people who would suffer.

“They’ve got no feeling or compassion or anything like that, when they make these decisions,” Lieseke said, his voice raspy with anger. “They just don’t care. Bush’s statement, ‘We know we’re gonna suffer casualties.’ What a cold statement to make. I know that my decision’s gonna get a bunch of people killed, but, oh well. And people like that, I say screw you. They view our kids as cannon fodder. That’s all. They just don’t give a damn.”

“Now you’re talking about the president,” I asked.

“President on down, and all of these elitists he has making these decisions, like Dick Cheney, and the super fucking multimillionaires send people into harm’s way. Bush has never had a hard day. His children have never known hardship. But it’s okay. Those aren’t his thoughts when you are getting other peoples’ kids killed. It’s just not a thought.”

Fred and Chelle Pokorney had different beliefs than Wade Lieseke. They were convinced Fred’s service as a U.S. Marine was going to make a difference in the lives of oppressed Iraqis and maybe even stop terrorism. Fred Pokorney’s convictions did not falter.

“Fred did believe in what he was doing,” Chelle said. “And I never doubted my husband. Never doubted him as a Marine or as a man. He was one of the great ones. He so loved what he was doing. That’s all I know how to say. Once you knew Fred, you just knew him, and you trusted him.”

The big Marine, though, was human, and he had his own fears. On a February morning of 2003, Fred and Chelle drove through the Carolina pines to the buses, which were to take him and other Marines to ships bound for Kuwait. He tried to be light-hearted, issuing Chelle her own set of orders, “Take care of Taylor and don’t wreck the car.” When they held each other to say goodbye at the base, Fred’s broad frame was quivering. Chelle did not know if it was the chill air, or apprehension at what lay across the ocean. She said she had never seen her husband shake before. As he boarded the bus, she had the recognition of something awful, which she wanted to deny and push out of her mind.

“I did have this feeling,” she said. “That I was never going to see him again.”

(Part Two: “Friendly Fire at the Saddam Canal” was dispatched at the same time as Part One.)