Brush Country

A Mystery that Changed History

(This newsletter is the rebirth of a project I started in 2017. My goal here is to offer information, insight, and maybe even entertainment. There will be personal experience included since I provide a point of view. But my focus is on this confounding state, its myths and realities. I will write about travel, literature, history, movies, politics, and just life its ownself under the Lone Star, and the broader influence of Texas beyond its borders.

It’s free to anyone who wants it, but those modest paid subscriptions, if you are inclined, can help fire the engines. Go ahead and be inclined. I’ll publish at least once a week, depending on interest, yours and mine. I will also post randomly with stories worth sharing and that are not part of the weekly newsletter).

“I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right, temporarily defeated, is stronger than evil triumphant.” – Martin Luther King

Leaving San Antonio and heading south toward Alice, Texas, Bill Mason had to be wondering about the arc of his journalism career. He had been to the top of his profession and was taking his wife and son to what must have felt like the end of the road. Alice was the seat of Jim Wells County, set in the middle of the rugged South Texas brush country, and could not appear to offer much to a veteran journalist.

William (Bill) Haywood Mason had earned a reputation as a determined and diligent journalist that stretched from Detroit to San Francisco, back to Chicago and down to San Antonio. His career started in 1919 at the Minneapolis Journal when he returned from service overseas in World War I. After a few years as a reporter and editor in Minnesota, Mason left for California and spent the next decade at papers in the San Francisco Bay area, including the San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco Examiner, Oakland Post-Enquirer, and the San Francisco Call-Bulletin.

Doughboy Mason home from the World War I with his future bride Harriet Stangland

Eventually, he landed at the Detroit Bureau of the New York Times before working in public relations. After agency work in Detroit and corporate PR jobs in Houston and Waco, Mason opened a public relations firm under his name in Mexico, which led to managing the 1946 election campaign of future Mexican President Miguel Aleman. According to the Houston Press, Mason said he had disputes with powerful lieutenants of the president and had to quickly leave Mexico. He landed as a copy editor at the San Antonio Light. The job was considerably less glamorous than his previous reportorial escapades, but Mason said he had been forced to leave most of his money behind in Mexico, and he needed work.

His peripatetic career and cumulative experiences had given Mason a catalogue of great stories, and he had in mind a book when he left San Antonio for Jim Wells County. He expected to end his career as editor and columnist for the Alice Echo. Geographically remote, politically obscure, and economically deprived, Alice was an unlikely home for a journalist with Bill Mason’s resume. The San Francisco Chronicle later described his reportorial doggedness by calling him an investigator “who took up where police work left off.” Mason was credited with “effective sleuthing” in numerous murder cases in the Bay area, which led to the capture and conviction of many dangerous criminals.

When Mason arrived in Alice in July of 1948, he was looking for a location that would remove him from the mad chase of big city journalism and dirty politics. Outsiders might have seen the South Texas brush country of Jim Wells County and assumed the churches and cantinas and vast ranches were a manifestation of a simpler way of living, a country innocence that was devoid of urban machinations.

Such an assessment was only partially correct. In fact, in the case of Alice and Jim Wells and Duval Counties, the perception was insidiously wrong. Mason, unfortunately, had stepped into an historical riptide, and the consequences of his timing and principles became a tragedy that deserves further scrutiny, and great remembrance.

A reporter with a sharp eye for irony and the fortitude to confront local power structures can often find a fulfilling career in a small town. Bill Mason, however, seemed destined for journalism’s grander stages. During the 1920s, when future Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren was the district attorney in San Francisco’s Alameda County, Mason did much of the “spade work” on an investigation of a paving graft and corruption ring. Mason later wrote in the Alice Echo that his reporting had sent about twenty officials, including the sheriff and a city commissioner, to San Quentin Prison. Warren, however, was not generous to Mason in his memoirs and offered a negative assessment, though he did acknowledge the reporter’s assistance in facilitating the testimony of a critical witness.

Mason endorsed an opponent of Warren’s in a future election because he believed that the incumbent DA did not believe strongly enough in full disclosure of information to the public. In one of the greatest unwritten ironies in American history, Warren, ultimately, became the chairman of a commission that bore his name and was established by President Lyndon Baines Johnson to investigate the Kennedy assassination. A huge body of research by historians and governmental bodies over the past half-century have proved the Warren Commission was effective only at ignoring evidence and covering up facts about JFK’s murder. Bill Mason’s journalistic analysis of Earl Warren had been painfully astute, decades in advance.

By ignoring evidence, the Warren Commission has prompted many investigators and conspiracy theorists to make a case that LBJ was a possible complicit actor in JFK’s murder and Bill Mason was to learn about the future senator and president through his job at the paper in Alice. Lyndon Baines Johnson began his long immoral climb to the White House with an election that was stolen in Jim Wells County just a few weeks before Mason began his new job at the Echo.

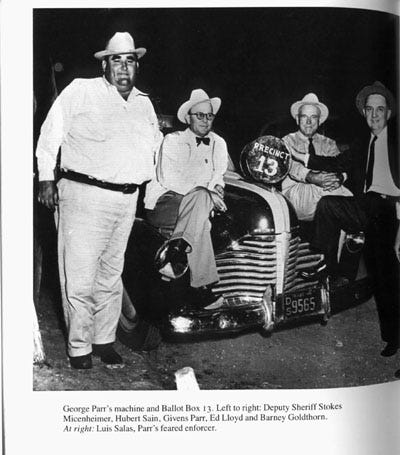

Mason did not know, nor could he, the complexity or power of the local political apparatus that had been set to work for LBJ by George Parr, a man whose administration was so corrupt and oppressive he was known as the “Duke of Duval,” a man who reigned politically and financially over the lives of impoverished immigrants and South Texans. Parr and his father, Archer, had maintained complete control over six counties for decades, manipulating businesses, election outcomes, courts, law enforcement, the expenditure and theft of taxes from all sources. They had built an empire that made them rich, and outside the law. Mexican Americans, fearful of his every move, had given Parr the nickname, “the sly possum.”

By 1948 as Mason made his way to Alice, LBJ had learned the methodologies of corrupt Texas politics. He had been previously defeated in a 1941 special election for the U.S. Senate by W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel, whose victory came from a series of late returns in districts where his political cronies controlled the ballot boxes. Johnson was chastened by his loss, but he did not forget how it had transpired. When he faced Coke Stevenson, a popular former governor, in a runoff for the Democratic Senate nomination, Johnson was determined to eliminate the risk of losing. And in an overwhelmingly Democratic state like Texas, a victory in the party primary ensured electoral success in November.

Mason and wife Harriet in South Texas

Johnson knew Parr’s reputation, and assumed he could be counted on to deliver late votes if they were needed to beat Stevenson. It was probably nothing more than a matter of money, or a guarantee of political protection or patronage. Parr certainly did not want outsiders sniffing around his operations, and if he elected a U.S. Senator, the odds of any investigation would be reduced because of the senator’s protection.

LBJ and his young sycophantic protégé John Connally went to San Diego, Texas, the seat of Duval County, to meet with George Parr and establish an insurance policy for Johnson’s win. The Duke did not need it explained to him how valuable it would be to have a U.S. Senator in his corner as he continued stealing tax revenues and rigging elections to sustain his power. The Duval County seat in San Diego was only ten miles from Alice, which made it easy for Parr to exercise as much control in Jim Wells County as he did in Duval. Holding back boxes to deliver late returns was not complicated for a political machine that had been orchestrating election outcomes for decades.

George Parr, the Duke of Duval

Parr turned the job over to two of his pistoleros, Luis Salas and Sam Smithwick. They were county sheriff’s deputies that delivered the muscled enforcement of the Duke’s decisions, which were often filtered through County Sheriff Hubert Sain. Salas wrote about the election cheating for LBJ years later in a document he turned over to LBJ’s biographer Robert Caro. Parr had chosen to make Precinct 13’s box disappear long enough to get a good fix on the number of votes LBJ needed to win. On the day of voting, Box 13 had 765 votes for LBJ and 60 for former Governor Stevenson.

The final tally was to become, arguably, the most blatant case of corruption in American electoral history and set the stage for future geo-political chaos that led to millions of deaths. There is no disputing LBJ’s presidency had positive outcomes that included the Civil Rights Act, Voting Rights Act, and Great Society reforms that were designed to lift lower income families. His legacy, however, will always be marred by his execution of a war his predecessor John Kennedy had decided to end.

The election that changed the course of history was still in dispute six days after polls had closed when Box 13 suddenly showed Johnson with 965 votes; Stevenson’s total had risen to only 62. The last 202 names on the voter tally sheet were in alphabetical order, the same penmanship, and written with the same color ink. Two hundred of them, many who claimed not to have voted that day, or were deceased, had unknowingly cast a ballot for LBJ. The future president won by 87 votes and took the title “Landslide Lyndon” with him into electoral eternity.

Stevenson argued before the state’s Democratic party, and in Texas district and federal courts, that the totals had to be discarded. The former governor, however, lost the legal battle when LBJ’s attorney, Abe Fortas, convinced a federal judge to intervene and order a shutdown of arguments in district courts in Alice and Austin. Johnson stole the July 1948 primary runoff, which led to the predictable November election to the U.S. Senate. Stevenson went back to his ranch on the South Llano River near Junction to spend time sitting by the camp fire.

Former Governor Coke Stevenson

Bill Mason, the new editor of the Alice Echo, wrote about the controversy with the same objectivity as the national reporters that had trekked to the brush country. His front-page stories were balanced and revealed no predisposition toward the notion of a stolen election, though few believed the results were legitimate. Mason only mentioned the controversy in two of his columns, which tended to focus on community issues. His primary targets were corrupt police officers and county officials, though he did not ignore the election that had placed his new hometown in the national spotlight.

In the six months Mason wrote his “Street Scene” column for the Echo, he was increasingly frustrated. His journalistic years had been spent pressing for full disclosure, but he was unable to get basic information from the sheriff’s deputies or the Alice police, which only prompted him to write more critically of institutional authorities. As the Duke’s corruption became clearer to the reporter, he urged citizens to demand investigations, and call upon the federal government to right what was wrong in their communities. Parr would have been outraged. The paper’s publisher, V.D. Ringwald was concerned by Mason’s confrontational approach with his journalism. Ringwald was taking the heat for Mason’s writing and had been confronted on the street by a couple of Parr’s deputies.

“I have a wife and small children,” Ringwald told Mason.

In the ensuing weeks, Mason’s columns lacked tension and controversy. On December 23, 1948, he wrote that he had been in the newspaper business for 29 years, and that he had learned to be, “…fair to all, do good if I can, and publish the truth, even if it hurt someone. If I can’t follow that creed, I leave. Last night, we learned we could not follow that creed here. We are all right as long as we do not tread on certain toes. We have. We can’t print anything that steps on those toes. We are leaving.” In that same piece, Mason indicated he was returning to San Antonio.

That was his last column, published on Christmas Eve, 1948.

Oddly, though, Mason was quickly hired by Alice radio station KBKI-AM, which was owned partially by George Parr, and he stayed in town. Going on the air at the 1000-watt radio station may have exacerbated Mason’s status as an outside agitator, however. Illiteracy rates were high in the brush country and far fewer people were able to read his newspaper columns than the number who understood what he was saying on the radio during his “Bill Mason Speaks” program. His criticism was also probably considered more acute because he was not born in the brush country. Outlanders were not welcome if they did not accept the way things were done.

Ed Lloyd, an attorney who was a co-owner of KBKI and a Parr friend, said, “Anyone not bred and born in the brush country is a stranger for many years.” Lloyd said that after living there twenty years he was often treated as an outsider.

Bill Mason could not have been oblivious to his situation. He had likely been given the job at the radio station so Parr and his generals might keep him under closer scrutiny. Unfortunately, Mason’s fate was determined, in part, by the fact that most people were beginning to get their information from radio in the 1940s, and the more he criticized, the greater his risk of harm. Mason certainly spoke of the Box 13 scandal on the air at a time when the Duke of Duval was worried there might be increased federal inquiries, but the gadfly broadcaster was more interested in local corruption, which he wrote about consistently when he was a columnist at the newspaper.

“I am agin ’em when they are wrong,” he wrote of the Alice police department. “I’m for ’em when they are right. I’m agin ’em when they won’t give me information. We should change the policemen or police chief or both.”

There was sufficient corruption in Alice, Texas in that era to keep busy a large staff of newspaper reporters. Bill Mason, however, was almost the only individual on the task, and sanity dictated a certain amount of trepidation. The Duke of Duval had been known to threaten tax increases for people who did business with his political opponents; he had critics falsely arrested for public drunkenness, and even had deputies block the parking lots of some establishments. In one instance, Parr let it be known that county welfare checks would stop to recipients that shopped at a particular grocery store. These were the stories that often went unreported until Bill Mason arrived in Alice.

More onerously, though, were the murders. When the Corpus Christi Caller-Times sent reporter James Rowe to cover the brush country counties, he said that an Alice doctor had told him there had been at least 103 suspicious deaths that he had counted. Coroner’s reports were brief and lacking detail.

The Box 13 scandal brought out of town national news media to Duval County and Rowe’s presence along with Bill Mason’s radio show had suddenly created an environment of accountability that had never existed in the “Land of Parr.” No one had ever asked questions of the Duke and his compadres, much less insist they answer.

Less than six months into his new broadcasting career Mason decided to step up his criticism of a system of rewards Parr and County Sheriff Hubert Sain seemed to have established to put money into the pockets of their deputies. Earlier that year in March of 1949, Sheriff Sain had already run out of patience with Mason for talking on the radio about a group of beer joints and dance halls that were fronts for prostitution and gambling. Sain and Deputy Charles Brand found Mason at a bowling alley and beat him after they got him to come outside into a parking lot. Mason described it on the radio as a “token beating,” during which his pants came off. Unbowed, the reporter hung his pants on a pole in the center of Alice’s town square and told anyone who wanted to fight him to meet him “under his pants.”

But he did not relent and resumed his attacks on Parr’s and Sain’s and corruption.

“The real answer is in the county,” Mason said in one of his broadcasts. “The hot potato is strictly in Hubert Sain’s lap. Here is a chance for all of you church people to make your influence felt. Form a committee and send people out to these places to see for yourselves what is happening. You don’t have to take my word.”

One of the deputies profiting from the arrangement, according to Mason, was Sam Smithwick, who was involved in the changing of Box 13 results to give LBJ the senate election and had probably made the infamous box disappear. Smithwick, whose father was an Anglo and his mother Hispanic, was unable to read or write English. He did, however, speak and understand the language and was livid when Mason began talking about him on KBKI. Mason took an entire week on the air to offer details about a tavern and dance hall, which had been built on Sam Smithwick’s land. He claimed it was a whorehouse and a gambling operation and that the deputy was getting a healthy cut of the considerable profits.

The transcript of Bill Mason’s last broadcast in Alice, Texas, which was apparently recorded, was published in the Houston Press at the end of July, 1949.

“I’m going to take the gloves off today in the prostitute situation, and start swinging. I have been told by my friends sometimes that I shouldn’t pick on hungry Hubert Sain. Maybe I shouldn’t but a situation exists in Alice, which he alone is in position to stamp out. Any of you can spend an hour on the south side and see the suffering and misery, which is being caused by operation of the dance hall girls. Dance hall girls who work, many of them on the property of Sam Smithwick, a deputy of Hubert Sain’s.

“There are nightly violations of the liquor control law. The officers of that state department have more to do than watch Jim Wells County. But it is the sworn duty of the sheriff to see that the state laws are enforced. But on Deputy Smithwick’s property, every night, the world’s oldest profession is plying its trade, heaping dollars into the pockets of the proprietor of the place. I charge here today that Sam Smithwick knows what is going on.

“I charge him with permitting it and not lifting a hand to stop it, but looking back over his score, what thing has he done besides sending another deputy to tear my pants off and try to scare me out of town. There is only one course open to you people who want a decent town. Insist that this thing be stopped. You may file a recall for impeachment proceedings. I am not too familiar with the law, but there is some way of getting rid of him. Or we can ask a special session of the grand jury and let them go into it. Or we can ask the federal government to come in and look over those incomes.”

No one is certain whether Deputy Smithwick heard that last broadcast, but court testimony indicated that Mason had told friends he was going to mention the lawman’s daughter on the air the next day in connection with the brothel. The day after that radio broadcast, the deputy found Bill Mason before the journalist was able to get to the radio station for his midday show. He was sitting in his car, parked in an industrial area of town, when the lawman Smithwick walked over and shot Mason with his .45 caliber service revolver.

Mason did not immediately die. The bullet apparently came close to his heart. Witnesses said he got out of his car, ran across an open field, and fell to the ground and bled to death. Deputy Smithwick drove himself to the county jail, walked in and put his badge on a desk, and went to sit in a cell until he was charged.

If Parr suggested to Smithwick that he shut up Mason, no one has ever discovered such evidence, and LBJ historian Caro has insisted “no link has ever been found” to connect the killing directly to the Duke of Duval. However, having the radio newsman talk about illegal activities had to be unnerving to the political kingpin, who had just lived through the federal hearings and media circus that had surrounded LBJ and Box 13. Parr might have feared more worrisome attention from investigators if Mason did not stop his assaults on talk radio. He had repeatedly called for federal authorities to return to Jim Wells County and prosecute the corruption.

Regardless, a silenced Bill Mason was good news for the Duke. Nonetheless, Parr, as a part owner of the radio station, might have simply fired Mason, though having him on the payroll was also a technique for control, which was how he handled Mexican workers in the county. People with families whose jobs are threatened tend to be compliant. There is also the real possibility Parr urged Smithwick to do the job and suggested he’d get him acquitted at trial. It’s just as likely the Duke turned his back on the deputy sheriff because he realized having one of his conspirators in Box 13 in jail for murder would make any witness testimony from Smithwick become suspect. Parr had Mason and Smithwick out of his hair, which ought to have been sufficient cause for a criminal investigation of the Duke.

Sam Smithwick had good reason to not fear prison. His unquestioning service and loyalty to Parr’s dubious operations probably felt to the deputy like an insurance policy. He knew the Duke’s control was absolute in the brush country and the murder case would have been heard before one of his long-time supporters, Judge Lorenz Broeter. Unfortunately for Smithwick, Broeder had been diagnosed with cancer and had to name a replacement. Judge Broeter defied Parr’s recommendation and appointed a man who had no allegiance or debt to Parr. The new judge moved the case to Belton in Central Texas, which did little to mitigate the tension surrounding the proceedings. Shots were fired at the prosecutor James Evetts when he parked his car, and, eventually, transcripts disappeared from the trial and the state appeals court hearing. Smithwick was a killer but it seemed something else was afoot.

Nothing Bill Mason had reported on the radio or in his newspaper column was untrue. During testimony, the state heard from a former deputy that he was paid $10 a week to deliver 70 percent of the profits of the brothel and gambling den to Smithwick. This would have been a perfect technique for Smithwick to provide Parr his share without any direct connection between the judge and the beer joint. The deputy’s niece was among several young women who admitted in court that they had met and “dated” men at the Smithwick establishment. Records introduced also proved Smithwick owned the property, a claim that was central to Mason’s reporting.

The death of Bill Mason made national news when he was killed in July of 1949. His story was on front pages across the country with headlines like the one in the Alice Echo, which read, “A Courageous Man Dies.” In a matter of months, though, Mason’s murder slipped into obscurity, possibly because he was a reminder of the uncontrolled corruption that sent LBJ to the U.S. Senate, and Alice was too geographically remote for reporters to spend much time poring over documents and conducting interviews.

Mason’s memory may still be making people uncomfortable in Alice. Researcher Mary K. Sparks wrote that she was talking to a friend of Mason’s in October of 1991 and the conversation was conducted in “hushed tones” and that the subject changed when “a waitress or anyone else came to the table.” Sparks also said that the publisher of the Alice newspaper told her he was still being reminded to “Remember what happened to Bill Mason.”

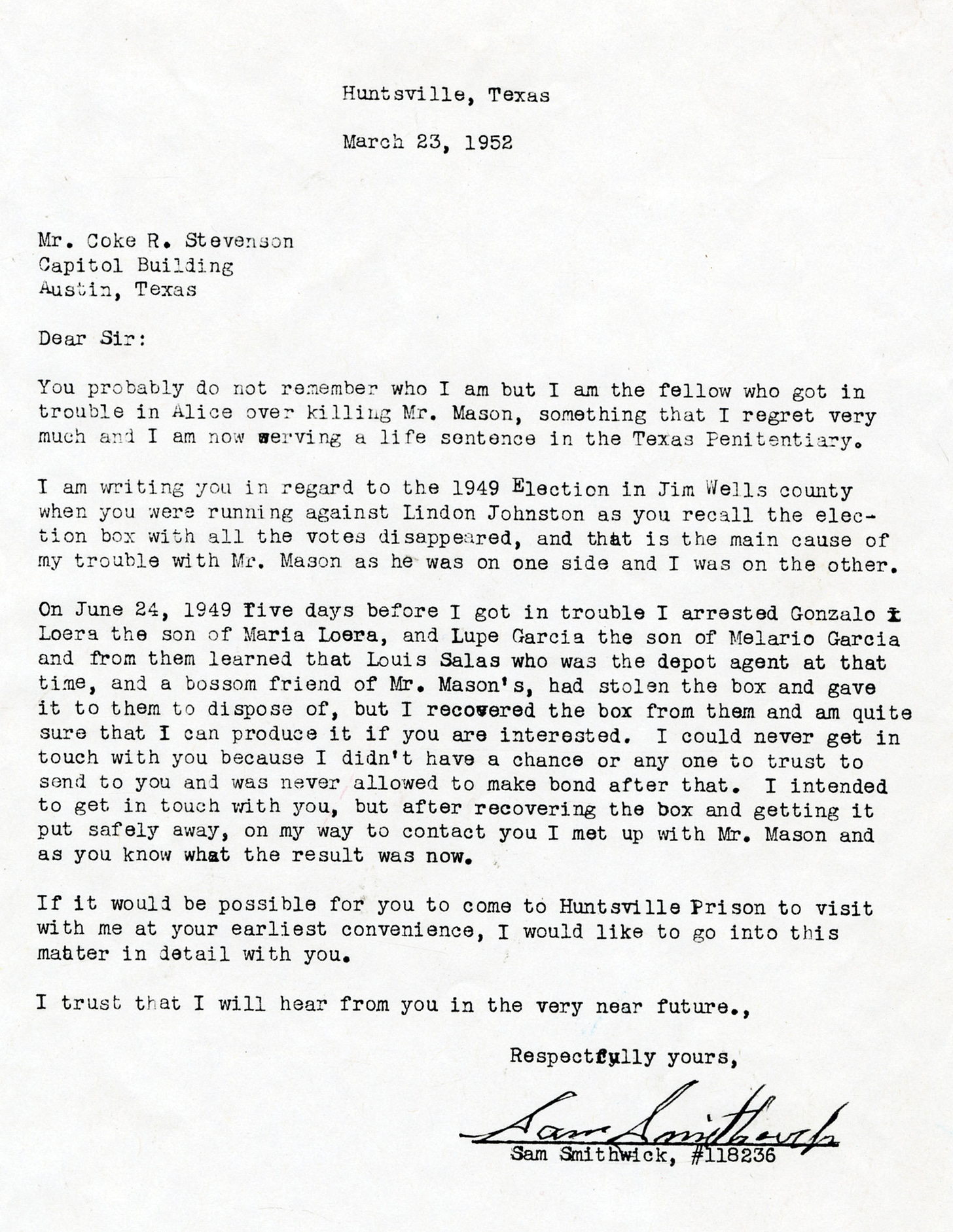

What happened to Sam Smithwick is even more mysterious and disturbing. Parr’s pistolero was sentenced to life in prison and, after about a year and a half, apparently began to resent that he was the only one from Jim Wells and Duval Counties that was being punished for illegal activity. Smithwick wrote to Coke Stevenson, the former governor who had been robbed of the senate seat by LBJ’s vote faking deal with Parr. How an illiterate man drafted the letter has never been explained. He might have gotten assistance from a guard who later told someone about the message Smithwick had sent to Stevenson. Outbound communications from inmates were often screened and censored before being dispatched.

The letter, which was later published on the front page of every daily Texas newspaper, suggested a new level of political intrigue. Smithwick claimed that Box 13 had been stolen and he had recovered it, and wrote to Stevenson, “I am quite sure that I can produce it, if you are interested.” In fact, he said he had already “recovered” the box and had “put it safely away” and was on his way to try to contact the former governor when he came across Bill Mason.

“If it would be possible for you to come to Huntsville Prison to visit with me at your convenience,” the deputy wrote, “I would like to go into this matter in detail with you.”

Box 13’s true voter tally, and firsthand testimony from someone involved in the fraudulent election, might have had the power depose LBJ as U.S. Senator and give the election to Stevenson, or at least prompt another special election. Smithwick had promised to name two Mexican Americans that had delivered to him the missing contents of Box 13 just five days before he had killed Bill Mason.

Stevenson, who had returned to the practice of law in Junction, Texas, left his ranch on the Llano River immediately for Huntsville. Enroute, he called the prison to notify them he was coming to interview Smithwick. The former governor was told there was no reason to continue his trip. The 62-year-old Smithwick, 6’4” and 280 pounds, was found with a noose made of twisted bed sheets around his neck and hanging from a crossbar of his bed.

The death of a convicted killer doing a life term in prison does not generate a lot of news. A few headlines were styled like one that said, “Lifer Commits Suicide.” There were rumors and hints among guards that Smithwick had been ordered killed because he could testify to the facts of the stolen election, and his letter seemed to make it clear he would after it was published statewide. In 1956, four years after Sam Smithwick had been found dead, the sitting Texas Governor Allen Shivers accused LBJ to his face of having Smithwick killed to prevent his public testimony about Box 13. Johnson, who certainly had a motive, was astonished to be called a murderer.

“Shivers charged me with murder,” LBJ told the Texas Observer’s Ronnie Dugger. “Shivers said I was a murderer.” Johnson did not take the opportunity to deny it.

Although declared a suicide, Sam Smithwick’s death remains mysterious given the timing and circumstances related to his letter and the pending trip of the former governor. LBJ biographer Robert Caro wrote in his four-part series of books “no evidence was ever adduced” to connect LBJ to Smithwick’s killing. Perhaps not, but there had been no real investigation. Caro gave the Smithwick story a few short paragraphs in his second book and only one sentence mentioned Bill Mason. There was sufficient reason to suspect LBJ and his lieutenants in connection with the Smithwick death, and there always will be. A forensic investigation all these years later may change nothing, but any pursuit of the truth in this case is worthwhile.

There will always be questions about the death of Sam Smithwick but a witness in court testimony during his murder trial left no doubt about what the deputy had done to Bill Mason. He was murdered for speaking the truth. Mason is still the only broadcast journalist in Texas history to be killed for doing his job, and was the second in American history, yet he has largely been forgotten. The contemporary craft of reporting is beleaguered by distortions and inaccuracies that are often prompted by pressures from cable news deadlines and Internet rumormongers. Consequently, remembering the best of journalists can provide an important perspective to the newcomers in the business. Reporting has always been about service, which was what Mason offered to Alice, Texas under the most difficult of circumstances.

Journalism needs to honor to the memory of Bill Mason, who refused to be intimidated and provided his community with important information to make decisions. The simplest commemoration would be for the Texas Associated Press Broadcasters, Houston Press Club, the Texas Headliners Foundation, the Texas Emmys, or even the Radio Television News Digital Association to name their “Reporter of the Year” awards after Bill Mason. He deserves a legacy because he was performing to a standard envisioned by a free press, and it cost him his life.

On his tombstone, not far from the former location of Sam Smithwick’s illegal business operation, are words spoken by the prosecutor of Mason’s killer. They reflect a purpose that has been fading from journalism but needs to be remembered, along with Bill Mason.

“He died because he had the nerve to tell the truth for a lot of little people.”

I are a reporter. I'm writing a screenplay on that one. Important historical moment that has never been given the light of day.

What a terrific read!