“One cannot be pessimistic about the West. This is the native home of hope. When it fully learns that cooperation, not rugged individualism, is the quality that most characterizes and preserves it, then it will have achieved itself and outlived its origins. Then it has a chance to create a society to match its scenery.” ― Wallace Stegner, The Sound of Mountain Water

I love roads. More accurately, I suppose, they are a kind of obsession. My fascination began in childhood. I can remember standing on the edge of the old Dixie Highway up in Michigan and being struck by the wonder that I might follow that stretch of concrete until it reached the famed states of the American South. I could start walking along the Dixie’s shoulder and its paved surface and I would be guided without error to another world.

The curiosity was amplified when the first length of Interstate Highway was completed near our neighborhood of Dixie Diaspora. I remember convincing my father to stop on an overpass to let me get out and look down on the passing traffic. The enhanced sense of mystery came from the fact that motorists were suddenly able to travel anywhere in the land without hitting a stoplight. They needed only to touch the brakes and pull off for fuel. My father, himself rather baffled by the Interstate system, did not grasp the idea of “merging” with traffic. Until he conceded his child better understood the new restricted access roadways, his tendency was to drive to the bottom of an onramp, stop, turn on his blinker, and look over his left shoulder for oncoming traffic before pulling onto the main lanes.

When I finished high school, I went straight to the highway for hitchhiking adventures to explore the American West. I was only seventeen that summer but I was more excited than fearful of who might stop to give me a ride. My transit west was awkward and comprised of many local rides down state and county roads. Nights I slept beneath overpass bridges or down a culvert or off in a field, distant from the pavement, and yet I had no second thoughts about my decision to wander. After I passed through Omaha with a trucker bound for San Francisco with a load of refrigerators, I knew the next day I was going to see Rocky Mountain National Park.

At Endovalley Campground, I put up my frail nylon tent, and arose the next morning for a hike up a dirt road carved in the mountainside. Old Fall River Road was mostly cut by young men using hand tools and working for the Civilian Conservation Corps during and after the Great Depression. I do not remember how far I hiked that day because there were no mile markers but every step took me higher into the Rockies and I slept when I ran out of energy after about ten hours. There was no sound at night other than the wind in the pines and a creek lightly gurgling nearby, from which I filled my canteen. Dinner was just two pieces of jerky but I awoke energized in the chill and tangy mountain air, ready for the walk downhill.

Fall River Road, Rocky Mountain National Park, 1926

The rest of the summer I caught rides in the back of pickup trucks, VW vans, Airstreams pulled behind Oldsmobiles, tractor trailers and flatbed haulers. I saw highways unfolding behind me or twisting endlessly over the hood of a stranger’s vehicle carrying me west through the Rockies, down into the Great Basin, up toward the Sierras and then the Pacific Coast of California. There was never a moment I was not excited and even in the aloneness of a sleeping bag on an empty beach or behind a boulder in a remote rest area, I was often too energized to even close my eyes. The country seemed to my teenaged mind to be held together by these veins of chip-sealed caliche road beds and reinforced “super slabs” that began connecting like national capillaries after the Eisenhower administration gave birth to the idea.

Eventually, I bought a used motorcycle with my $1.75 an hour wages cleaning tables in a dormitory cafeteria, and a nice check I got from ten days working on an assembly line at the Fisher Body Plant in Flint. The facility was made famous in Michael Moore’s (no relation) initial documentary, “Roger and Me,” when he filmed its demolition after providing thousands of jobs to our mutual hometown. I think the only time I ever made my father happy was when I told him I had been hired at the factory, which was his life’s work. My job was to take metal ashtrays and pop them into plastic door moldings as cars slowly edged past my spot on the line. I was able to walk back to where the doors were first hung and get almost an hour’s worth of tasks accomplished in about ten minutes. When I returned to my station, I stuck my nose in a book and checked on passing vehicles every thirty minutes, just to be safe.

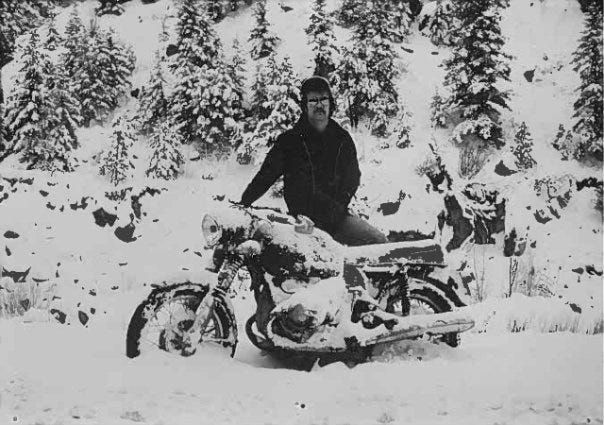

The union paycheck for my ten days was more money than I had ever encountered, and was too much of a temptation. The total, when added to busboy wages, made me comfortable purchasing a used 1968 Honda CB 450 motorcycle at a dealership near the university. After immediately quitting my job without telling my father, who was no longer married to my mother and living elsewhere, I saved up some gas and food money, and went searching once more for any road west. The bike was light and fairly fast for its slight displacement and I played the fool by sitting close behind semis on the Interstate, drafting in the air vortex off their trailers. I needed to barely touch the throttle to maintain highway speed while I hung onto the wind currents curling off the big haulers. I did not want to ride the Interstate but it was the quickest route to the mountains where I could barely wait to camp by the Colorado and the Roaring Fork and the Gunnison and Green Rivers and sleep on the ground beneath the stars up at the Great Divide near Loveland Pass.

The ensuing years, which have seemed of late to roll by faster than the miles, led to a stream of different motorcycles. I wandered six months on a Harley Sportster 883. The bike was black on orange and was a commemorative Milwaukee edition put out by the Davidson family after they purchased the company back from the AMF Corporation, which was demonstrably better at making bowling balls than motorcycles. Only 600 of the Sportster models were available, and I ended up owning two because my first purchase was totaled. Riding a curve on the Old Military Highway outside Omaha, my wife and I hit an oil slick and found ourselves airborne over a median and sliding across the oncoming lanes. There was no traffic, but the Sportster was totaled, and with the insurance check I bought the other one that had just arrived at the same dealership. Within a week, I was riding down the Front Range of the Rockies, making for Raton Pass, Santa Fe, Taos, the Grand Canyon, Mogollon Rim, the red rocks of Sedona, and the Valley of the Sun.

I went even further west in later years. During my sixtieth, I flew to Perth and rented a BMW GSA 1200 dual sport bike for a transcontinental run across the Outback and into Sydney. The 30-day ride still spins in my memory like an HD video. Australia is a vast continent the size of the U.S. with less than 30 million inhabitants, and the majority live along its magnificent coastlines. I went south out of Perth to the Margaret River Valley and the wine country before camping on the Blackwood River and riding down Cape Leeuwin, which separates the Pacific and Indian Oceans. The route chosen then went back north to the forest of giant Karri trees, among the tallest hardwoods on the planet. The overgrowth in the canopy was so dense the midday darkness caused the instrument lights to come up on the bike. Before nightfall, my tent was pitched on the ocean sand just west of Esperance, a remote and idyllic town set on palisades above the cold currents off the Antarctic that made me think of what San Diego must have been like before the condo builders and road pavers had arrived.

The track across the Outback and the Nullarbor Plain was straight and true, a 90-mile stretch of which was said to be the longest line of curve-less roadbed on the planet. Motorcyclists will tell any listener that they love twisting roads but the unvarnished actuality is that we are mostly seduced by hallucinations of unending pavement taking us toward whatever might beguile beyond the horizon. A road sign as I entered the Nullarbor urged caution because of wombats, kangaroos, and camels, but I rolled up the throttle making for a roadhouse in Caiguna where I hoped to sing “Waltzing Matilda” with Aussies celebrating their Independence Day. Instead, I was greeted by a warning sign outside the campground’s showers to make sure to close the door because snakes were known to “slither into the ablution block for moisture.” My adventurous tendencies were chastened by natural facts, especially when I entered the pub and saw two colorful laminated posters listing the world’s most deadly snakes and spiders inhabiting the Aussie environment. I hurried back to make certain I had zipped my tent flaps shut.

The Nullarbor Plain, Central Australia’s 90-mile Straight

I went up and down the Ayre Peninsula, slept beneath a Eucalyptus tree on a grassy slope overlooking the ocean and a seafood stand where I had underestimated my capabilities for consuming raw oysters from a tidal pool across the road. Eventually, I followed a one hundred mile dirt trail through the Grampian Ranges, down along the Limestone Coast, the legendary Great Ocean Road, through Melbourne, traced the Snowy River to take me up over the Snowy and Blue Mountains and back into the chaos of Sydney, one of the world’s most beautiful cities. At one point, I turned down a gravel track off the Great Ocean Road and parked the bike near the edge of the 1200-foot cliffs demarcating Australia’s southern continental shelf. There were no fences or warning signs. Only personal judgment saved your soul from a tragic end. I looked down and saw two sharks feeding in the foaming and shallow waters beneath the toes of my boots. A few feet away, I noticed a barely worn pair of shoes, abandoned and sitting side-by-side, facing the cliff, as if someone had taken them off, neatly sat them at the precipice, and, barefooted, stepped off into their eternity.

Australia’s Southern Continental Shelf

There are too many road stories to even begin detailing. The rides I have enjoyed the greatest are worth mentioning, though. These include California’s Pacific Coast Highway, hugging the coast from San Diego north to Oregon, edging the L.A. Basin through Santa Monica and Malibu and then up to the glories of Ventura and Santa Barbara and Pismo Beach to Monterrey and Big Sur. A completely different experience comes when the snow melts along the U.S. - Canada border and it becomes safe to motorcycle up the Going-to-the-Sun Highway, where spectacular as an adjective has its definition stretched around every bend in the road. Back to the south along the Mexican border in Texas, Ranch Road 170, known as the River Road because it follows the water course of the Rio Grande between Terlingua and Presidio, is like riding on a paved roller coaster through a pre-Cambrian landscape where the lava appears to have only recently cooled and the vast mesas might hide dinosaurs. Turn back north and run to Colorado and Rocky Mountain National Park to make your way to Trail Ridge Road, the highest elevation of pavement in this country. No matter how hot the summer, to the west you will see the perpetually snow-capped peaks of the Never Summer Mountains. Get further west and into Utah and ride toward Canyonlands National Park and Monument Valley on Highway 191. Park by the side of the road in the darkness and listen to “the music of the spheres.”

I could go on, but this is not the time. I am going for a ride.

Never Summer Mountains, Colorado, June, 1973

A wonderful travel essay. Makes me itch to get on the road. “Ablution,”Love it.

There is nothing better to be on a road along the Border with no cell service, John Prine, Guy Clark, andTownes Van Zandt CDs with a journal.