I am sitting next to the Platte River in Nebraska, watching the morning light on the water. This is not the kind of place that ever gets much attention among the political and media elite of the coasts. There is no location more solidly definable as the “flyover” than Central Nebraska. I have long been drawn to this part of the country, however, for its epic history, which is too often relegated to back chapters and collegiate essays. My sense, though, has consistently been that the existential struggle to define America, right up to its present day, began among the cottonwoods lining the shore of this mostly placid river.

By the time wagon trains and pioneers bound for Oregon and Utah had begun following the water course of the Platte west toward the Rockies, the U.S. had already been ignoring the lofty principles defined in its founding document. Much of the economy was generating profit and functionality on the backs of slaves brought to these shores from Africa. The rationalization tended to be that there was neither the manpower nor the will to do the farming and perform the labor needed for a mostly agricultural economy to thrive and deliver prosperity. Even with the vast expanse of arable land east of the Mississippi River to provide abundance, the European settlers wanted more and their government was willing to provide what they were demanding.

If slavery was their manageable sin, genocide was not an improbable outcome when it was framed as survival on the trail. Initially, there might not have been an intention to eliminate the indigenous peoples of the Lakota, Kiowa, Apache, Comanche, Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapahoe, Cherokee, and all the other tribes of the plains states. Their end, Americans argued, was an inevitable consequence of Manifest Destiny, the belief that white Europeans and their progeny had a right to any land they wanted to settle in the West. When their wagon trains were attacked by Indians as they traced the Platte River toward the sunset, they killed as many as possible before they themselves were destroyed. The Indians were characterized as savages for protecting their ranges from intruders and the Americans were portrayed as brave pioneers.

I have always thought it was a bit facile for historians to argue that cultures have been overrunning one another for centuries. While that is factual, genocide, even in ancient, less educated times, was not as likely, or preferred, as some form of assimilation. Federal government policy in the late 1800s in this country, though, was to allow pioneers to stake out settlements and claim land to farm and ranch, and, ultimately, to protect. Indians were viewed as a pestilence in the path of progress and plenty, and, as such, were to be eliminated, if they could not be accommodated. Incidents of depredations, where the Comanche or other tribes might sneak up on homesteaders to rape, kill, kidnap, and burn, only served as proof of their inhuman nature to the wider American culture.

Westward expansion was very much about dying. While there is a fairly accurate record of the lives of the white pioneers, the number of Native Americans who were killed has never been estimated. Nonetheless, the mortality rate from a clash of cultures, disease, and accident has made this river, where I sit staring at peaceful waters, into what has been called the longest graveyard in the world. About 350,000 people made the overland journey toward Oregon and 1 out of every 10 died en route. The estimate is that the 35,000 dead add up to a grave every 80 yards along the 2000 mile trip. The expeditions began in 1843 at Independence, Missouri, and continued until near the end of the Civil War in the mid 1860s. There are surely unmarked graves and the hopeful bones of lost souls a short walk from where I am taking the morning air.

Our foundational conflicts between greed and humanity came together with tragic and historic timing that still seems to not have had its importance properly measured. In November of 1864, William Tecumseh Sherman had completed his conquering of Atlanta and was conducting operations during his famed March to the Sea while Abraham Lincoln was finishing his successful reelection campaign for the presidency. The United States had shed great blood and expended much treasure to move closer to the document defining its origins. The ambition was to make all people free under the law and end slavery. Culturally, though, equality was at least a century distant, and even today remains elusive.

The noble ambition of freedom for African slaves and their descendants was subjugated by the horrors unfolding in the West. A few weeks after Lincoln’s reelection as Sherman’s troops were approaching the Atlantic, the 1st Colorado Infantry Regiment of Volunteers and the 3rd Colorado Regiment of Cavalry moved to attack a peaceful Indian village at Sand Creek in the southeastern corner of what was to become the future state of Colorado. The native village was comprised of about 750 Arapaho and Cheyenne, led by Chief Black Kettle, and had been suing for peace at nearby Fort Lyon.

Chief Black Kettle

What happened at Sand Creek became a study in the duplicitousness of American military forces and government during western expansion. John Evans, the territorial governor of Colorado, had issued a “friendly command” to all Indians in the territory to approach Fort Lyon for supplies and “safety,” but Black Kettle, and the other chiefs in his village, were aware that the U.S. Army had been ordered to shoot any Indians within sight of Fort Lyon. The hungry natives camped by the creek, whose number included about 250 women, children, and elderly, were hoping for permission to hunt without being hunted. Instead, on that cold November morning in 1864, they were wantonly murdered by the U.S. Military under the command of John Chivington.

Chivington was acting without orders, but beginning at around 6:30 a.m., his troops opened fire on unsuspecting and sleeping Cheyenne and Arapaho people. The troops were not satisfied with simply killing and began an eight hour rampage that was characterized by inhuman mutilations and torture. The only company of soldiers not to participate was led by Captain Silas Soule, who stood down at a distance, and watched as women went to their knees to beg for their lives, and children were struck dead with axes and swords. Soule, a decorated veteran in the Civil War and the Battle of Glorieta Pass in New Mexico, later wrote a letter to a friend, describing what he had witnessed.

“I tell you Ned it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized. One squaw was wounded and a fellow took a hatchet to finish her, she held her arms up to defend her, and he cut one arm off, and held the other with one hand and dashed the hatchet through her brain. One squaw with her two children, were on their knees begging for their lives of a dozen soldiers, within ten feet of them all, firing – when one succeeded in hitting the squaw in the thigh, when she took a knife and cut the throats of both children, and then killed herself. One old squaw hung herself in the lodge – there was not enough room for her to hang and she held up her knees and choked herself to death. Some tried to escape on the Prairie, but most of them were run down by horsemen. I saw two Indians hold one of another's hands, chased until they were exhausted, when they kneeled down, and clasped each other around the neck and were both shot together. They were all scalped, and as high as half a dozen taken from one head. They were all horribly mutilated. One woman was cut open and a child taken out of her, and scalped.”

No count was taken of the dead but the estimate was said to be about half the population of the Indian encampment.

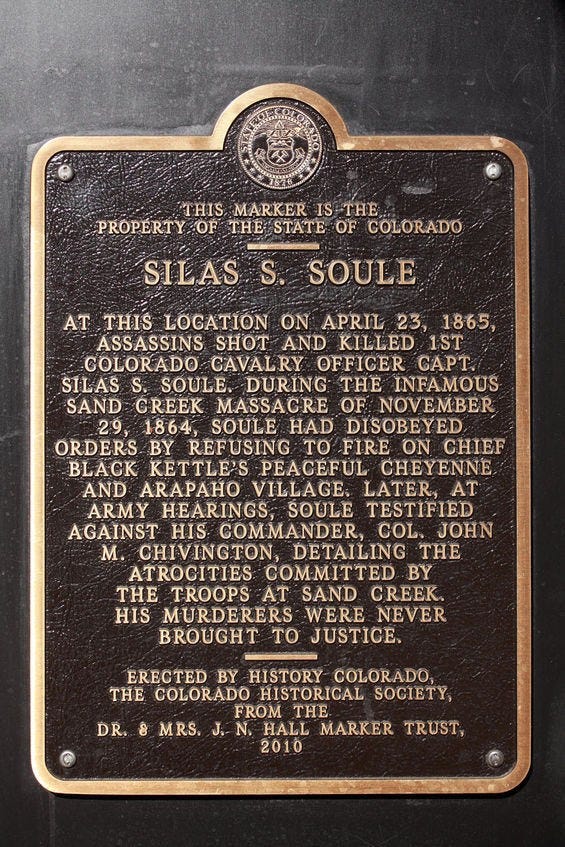

Captain Silas Soule, U.S. Army, Colorado Territory

Soule had come from an abolitionist family and had helped slaves on the Underground Railroad. When an inquiry was launched into what became known to history as the Sand Creek Massacre, he testified against Chivington and the other commanders who had indiscriminately killed Indians that had had been seeking peace with the white settlers. In January of 1865, after getting married, Soule was assassinated on the streets of Denver. His killers were known but never brought to justice, though it is assumed they were connected to elements of the U.S. Army who had been angered by his eyewitness accounts under oath and his refusal to participate in the slaughter.

Captain Soule had been involved in two previous attempts to define a treaty with the Arapahoe and Cheyenne tribes and had previously met in Denver with military officers seeking an accommodation to keep settlers, travelers, and railroad surveyors safe from attack. Those councils were probably called in an attempt to clarify the first Treaty of Fort Laramie, signed in 1851. The Plains tribes did not understand boundaries and guidelines in the agreement and continued to hunt where there was food and resist intrusions by wagon trains of white settlers. A few years after Soule was murdered, the second Fort Laramie Treaty was signed, which gave the Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapahoe the Black Hills of South Dakota in exchange for safe passage for over-landers and railroad workers. Fort Laramie, which was the second base established to provide protection on the Oregon Trail, was later burned to the ground in celebration by the tribes.

The Americans had been forced to the negotiation table by Chief Red Cloud. His band of Oglala Sioux terrorized miners, wagon trains, and any immigrants passing through the region because their appearance was viewed as a threat to the buffalo herds critical to the lives of native peoples. The U.S. government had tried to get Red Cloud to sign a non-aggression treaty in 1866 at Fort Laramie, but he refused and declared war on all whites entering traditional Sioux hunting grounds. Numerous battles occurred and Captain William Fetterman led what was described as a “relief party” into that stretch of the Oregon and Bozeman trails, and neither he nor his men were ever again seen or heard.

The success of Red Cloud and his braves undoubtedly prompted the need for a signed agreement to protect westward expansion on the continent. In exchange for safe passage, Washington agreed to allow the Sioux to keep the sacred Black Hills and most of their ranges west of the Missouri River. Reservations were described and every tribe accepted terms in the difficult negotiations. Treaties are, of course, only words and require convictions to give them force and meaning. Any chance of that dissipated when gold was discovered in the Black Hills in 1874 and miners raced across the prairie in search of mineral fortunes. The Fort Laramie Treaty that had been signed in 1868 became as irrelevant as every other agreement the U.S. government had made with indigenous tribes.

Washington made no real attempt to stop the gold rush, which was responsible for beginning the last of the Plains Indian wars. In fact, the expedition that found the first deposits was led by Civil War General George Armstrong Custer. Miners panning for gold were, predictably, attacked by the Sioux tribes. During previous decades, the U.S. military kept trying to reduce the Plains peoples to reservation residents, and they could not be effectively contained; especially when important treaties were violated and the white men could not be trusted. Custer, a blonde and ambitious dandy who was said to have presidential aspirations, mustered up a military expedition to end all Indian resistance; instead, it ended him, and his soldiers at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

Ultimately, the great tribes were corralled on reservations, impoverished by an inability to adjust to the white culture of sedentary farming and commerce, and angry that a treaty they had signed with the U.S. as another, and equal, sovereign nation had been abrogated. They held a legal document that said Washington recognized the Black Hills as belonging to the Sioux nation. The loss of the Black Hills was never acknowledged or recognized by the Sioux tribes, and they kept suing the federal government for its return. In 1979, an appeals court ruled that the tribe was entitled to an award of $17.5 million for the land, which was to include 5% interest accumulating since the year 1877. The total award was $106 million dollars.

The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in an 8-1 decision that the tribes were owed the sum in recompense for the government’s taking of the Black Hills even after signing a treaty. Writing for the court’s majority, Justice Harry Blackmun said in the 1980 finding:

“In sum, we conclude that the terms of 1877 Act did not affect mere change in the form of investment of Indian tribal property. Rather, the 1877 Act affected a taking of tribal property, property which had been set aside for the exclusive occupation of the Sioux by the Ft. Laramie Treaty of 1868. That taking implied an obligation on the part of the Government to make just compensation to the Sioux Nation, and that obligation, including an award of interest, must now, at last, be paid."

The court’s decision was not viewed then, or now, as even a moral victory. The Sioux considered themselves as much of a nation as the U.S. at the time the Treaty of Fort Laramie was signed and they do not acknowledge the jurisdiction the Supreme Court claims in settling their case. How can one nation have the authority to decide what is fair to another? Money is not the issue, either. The Sioux still want the return of the Black Hills. One nation cannot arbitrarily take property belonging to another and determine a valuation and pay it at a later date without violating international convention. Native Americans have argued, legally and morally, the Black Hills were never for sale. With interest, the original damages have grown to be worth more than $1 billion dollars, but the tribe has never accepted any check, even though the remaining descendants of the Plains Indians continue to live in crushing poverty.

This history of my country has haunted me as much as it has fascinated. I had read long ago of Captain Silas Soule and his fate and arriving on the green banks of the Platte in Nebraska in recent days brought back up his memory. No public school student in America has probably ever heard of Soule but his legacy ought to be taught to everyone who considers themselves a citizen of the U.S. There is no way to avoid contemplating what might have happened to create a different American West had there been more soldiers like Captain Soule, who defied orders that were immoral.

There is a modest plaque memorializing Soule at the intersection of 15th and Arapaho streets in Denver, though it gets little notice. There ought to be similar historical markers across the land for presently anonymous men and women who said no to wrongs, who refused to kill at My Lai in Vietnam, who defended people being abused because of the color of their skin, resisted participation in military invasions that were about nothing but oil or another country’s natural resources, or stood up to a president with dictatorial inclinations and told him we live in a democratic republic and stealing the presidency is a crime. We need as many statues to those souls as we do to war heroes. They are equally as important to who we are as Americans. I have always found it worthwhile to contemplate the courage of Captain Silas Soule, who was unflinching in his refusal to participate in rank evil.

His story makes me think of what my country might yet become.

Thank you for pulling back the covers on our outrageous history. Murdering thieves cast as explorers, while those trying to protect their land and lives labeled savages. We need more truth and more recognition of the truly brave ones, as you said. One of my grandmothers had enslaved parents, the other grandmother grew up on a reservation. They lived to experience better lives than their parents, but I know they had incurable emotional scars.

Our Constitution exhibits our idealized beliefs. But this quote from the film Alien Nation says it best about our ideals: “You humans are very curious to us. You invite us to live among you in an atmosphere of equality that we've never known before. You give us ownership of our own lives for the first time and you ask no more of us than you do of yourselves. I hope you understand how special your world is, how unique a people you humans are. Which is why it is all the more painful and confusing to us that so few of you seem capable of living up to the ideals you set for yourselves.”